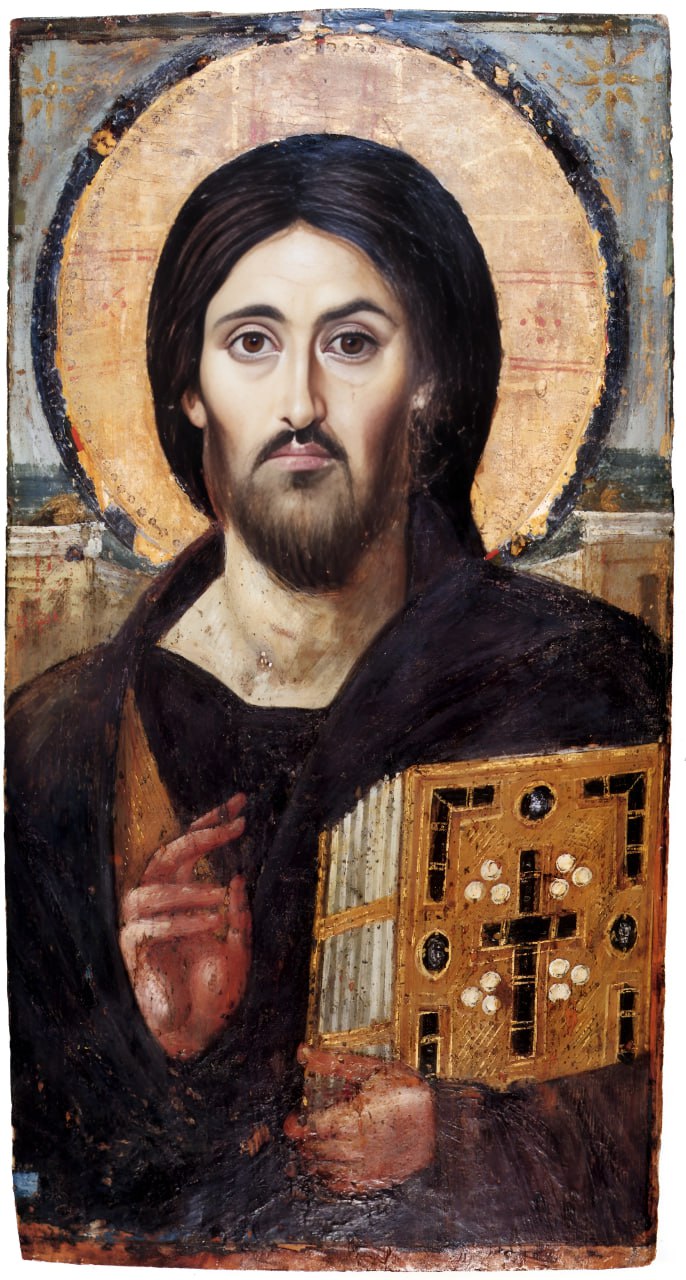

Christ Pantocrator (6th Century)

Christ Pantocrator (6th Century)

“There is so much talk about being offended by christianity because it is so dark and gloomy, offended because it is so rigorous etc. But it would be best of all to explain for once that the real reason that men are offended by christianity is that it is too high, because its goal is not man’s goal, because it wants to make man into something so extraordinary that he cannot grasp the thought.”

-Søren Kierkegaard

“Eventually your intellect, at a loss where to turn, is overwhelmed by dejection and laziness and forfeits all its spiritual progress. Then in deep humility it sets out once more on the path of salvation. Labouring much in prayer and all-night vigils, it uproots the causes of evil within itself through humility and confession before God and our neighbour. In this way it begins to regain the state of watchfulness.”

-St. Mark the Ascetic

Volume 4

Chapter 3: The Awakening

The Chosen

I promised myself that I’d use this session to immerse myself in the movie alone, and use most of the remaining time to listen to music. I wanted to experience the experience, rather than interrupt it to philosophize it away. I can always write later, once I’m coming down and sobering up. But that plan has largely failed—I just can’t help it. As I was watching the episode, I desired nothing more than to uncover the truth of this world, to understand what actually happened. It is clear that the story of Christianity is far from untainted. Many events within it have likely been mythologized, altered over time, or even fabricated entirely. Like everything else that enters the stream of history, Christianity is subject to the forces of time: bias, political influence, errors in translation, the distortions born of human agendas, and innocent human mistakes. These forces have accumulated over centuries and millennia. Yet, from the very depths of my being, I perceive that there is something profoundly true at its core—a kernel of truth that remains unshaken, despite the muddled layers that history may have covered. Beyond that core, however, the lines blur.

I find myself wrestling with the inability to distinguish with certainty what remains genuine from what has been obscured or reshaped through the centuries. Watching this film evokes in me an almost painful longing to unearth those obscured truths, to meticulously separate the authentic from the fabricated, the factual from the falsified. It’s a profound desire to dissect and discern, to bring light to what has been hidden beneath layers of historical distortion or misunderstood through the ages. I yearn to deeply understand the historical reality of Christ’s life, to trace the actual events as they might have unfolded, untouched by myth or alteration. Despite the errors, if one can hold confidence that not everything is false, and that something true persists, the question then becomes: what is the essence of that truth? At its heart, it all comes down to identity. What is the identity of Christianity? What defines true Christianity, stripped of the fragments left behind by political agendas, the distortions of history, and the biases of time? What is the diamond—the enduring, unshakable core—buried beneath all the layers of dirt that have accumulated over centuries?

One area of theology suggests that the path of theosis is not merely an optional pursuit for human beings but an essential part of our very nature—an integral component of what it means to be fully human. And this theosis is not purely a moral endeavor. It is inherently theological, deeply connected to the understanding that it is not simply about pursuing the highest Good, but about being in relationship with the very source of Being itself—the creator as the creator. But how can one know that this is indeed the source of Being? The answer seems to demand irrefutable evidence—something that only the ultimate source of Being, the most powerful of all, could achieve. And that evidence is the act of giving life itself. I tried, with every fiber of my being, to avoid getting caught in the endless loop of the Resurrection, as I did last time. And yet, here I am again. The Resurrection is miraculous not just because it defies natural laws, but because it embodies life at its core. This is a perspective I hadn’t fully considered before; I was always too fixated on its supernatural dimension. Yet, rethinking it as fundamentally life-giving begins to make sense—it encapsulates the essence of life itself in its most profound and awe-inspiring form.

Modern science, of course, dismisses the notion of life as a miracle. It regards such a concept as a relic of its historical triumph over vitalism, seeing life as a fully explained biological phenomenon. However, I’ve always felt that life cannot be fully reduced to biochemistry. It must also be linked to consciousness—the intangible, subjective dimension of existence. Consciousness seems to trace its origins back to the very roots of the evolutionary process, weaving its thread through every stage of development. This realization raises a deeper, more unsettling question: what brought consciousness into being in the first place? Its emergence feels inexplicably miraculous. Philosophers of mind within the materialistic tradition often invoke the concept of emergence to explain consciousness. According to this view, consciousness arises from complex neurobiological processes. But this explanation is far from satisfying. How does a non-physical phenomenon—characterized by subjective experiences and qualia—arise from purely physical substrates? The materialist framework struggles to identify the precise conditions under which consciousness manifests, as it seems to appear “out of thin air” once biological complexity crosses a threshold. This leap from non-conscious to conscious feels arbitrary, lacking a coherent mechanistic basis. At best, it resembles an act of faith masquerading as scientific reasoning.

Panpsychism, while not without its challenges, offers a more plausible framework. It posits that consciousness, or at least proto-consciousness, is a fundamental property of all matter rather than an emergent feature of complexity. This view eliminates the problematic leap from non-conscious to conscious by proposing a continuous spectrum of consciousness. Even elementary particles, under this framework, possess rudimentary forms of experience. These experiences grow increasingly complex and integrated within larger, more intricate entities. Thus, consciousness does not abruptly “arise” but exists inherently, being part of the very fabric of the universe. If consciousness indeed permeates all of existence, then the ancient mystery of life transforms into the mystery of consciousness itself. By embracing this perspective, we bypass the problem of explaining how consciousness arises from matter, as matter is imbued with consciousness from the outset. Yet, this shift demands a deeper explanation: why does consciousness exist at all? But then we’re back to trying to explain existence as such. Our inquiry moves beyond neuroscience to philosophy, and beyond philosophy to theology. Evolutionary biology is indispensable in explaining life’s development, but it falls short of addressing the foundational questions. With this in mind, it seems less unreasonable to consider life a miracle, as theologians have long claimed. From this perspective, the divine replication of such a miracle, as embodied in the Resurrection, no longer feels utterly inconceivable.

Whenever I take LSD, the memory of God always becomes clear. It is a bizarre experience. Each time, I am struck by the same realization: ‘Ah, yes. How could I have forgotten?’ As if it’s a completely obvious and self-evident truth, that I myself cannot believe I could have ever forgotten. As if you forgot your own wife, husband, parent, or child. Yet, each return to sobriety brings with it a lapse in this divine recollection, an ongoing cycle of remembering and forgetting. In this context, enlightenment can be seen as an act of remembrance—akin to what is referred to as “sati” in Buddhist traditions, a continual returning to awareness. As if you were Enlightened all along, you just forgot, somehow. In the same way that Plato’s notion of innate knowledge, as illustrated in his theory of anamnesis, suggests that learning is not the acquisition of new information but the recollection of truths already known to the soul at a deeper, pre-existing level. This idea is famously demonstrated in the Meno dialogue, where Socrates guides a slave boy through a series of questions about geometry. Without having been formally taught mathematics, the boy arrives at correct conclusions about the properties of a square simply by answering Socrates’ carefully structured questions. For Plato, this serves as evidence that the boy was not learning something new but rather remembering knowledge that his soul had already encountered in a prior existence. This cyclical nature of memory and forgetting underscores why rituals and traditions are so vital; they serve as enduring anchors of memory. They not only maintain an individual connection to the highest possible Good but also reinforce this memory across communities. As such, rituals and traditions are not merely personal practices but are societal stabilizers, linking us to the sacred itself.

As I listen to a Serbian chant titled The Second Coming of Christ, I’m enveloped in a profound sense of understanding about life and the world. Not just an anchor, but the ultimate anchor—it resonates with me deeply. I wish I could wear it like my cross—keeping it as intimately close, directly touching my heart and piercing the core of my soul. On one level, it seems regrettable that music cannot be physically worn, always present to continually bestow its benefits. But then I realize—I actually can carry it with me. In the past, music was a privilege of the elite, accessible only to a few and typically experienced in sacred spaces like churches, where it served as a reminder of the divine. Now, in stark contrast, technology allows me to access this sacred chant anytime at the press of a button. If this chant aligns so deeply with my essence, why not immerse myself in its presence as often as possible? Why forgo the sea anchor and risk drifting at sea? To some degree I already have using the anchor, although often not with such an explicitly existential goal. I’ve been somewhat obsessed with these kinds chants lately. But nevertheless it’s a good reminder to use what we can, as often as we can, in order to “remember”.

It’s crucial to note that my affinity for this Serbian chant isn’t because it is, by some divine mandate, the supreme chant among all. Instead, it acts as a portal to remembrance. And just a particularly powerful portal in this moment, for whatever reason. Such chants and the music accompanying them ultimately guide us towards the same destination: Christ. However, their role isn’t merely to point directly to Christ but rather to lead us toward the highest Good. If this were not the case, it would be entirely unintelligible to non-Christians, which it is not. However, through deep contemplation of this highest Good, one invariably encounters Christ. Yet, our engagement isn’t limited to this single chant alone; because Christ allows for multiplicity to flourish. Variety itself becomes an eternal source of joy.

As I typed the previous paragraph, I initially wanted to write that “variety is an eternal source of life towards the purpose of His worship”. However, I caught myself mid-thought, halting as the words began to take shape. I hesitated, concerned that such a phrase might sound overly religious, too esoteric or opaque to the reader. In response, I moderated my expression, reshaping it into what I presumed would be a more universally palatable form. But that wasn’t the truth. It was an attempted expression of the truth, corrupted and diluted for the sake of accessibility. But I need to remember that I should not concern myself with the average person. This book is not for them; it is for me and me alone. Anything else is a surplus that may or may not come.

This moment of correction felt profound, as though it was a fleeting embodiment of the entirety of Being—a singular, crystalline instant where the harmony of truth became manifest. In that specific nanosecond, my Being expressed truth itself, yet something shadowed it, a corruption I could not immediately name but instinctively recognized. It was as though a dissonant note had intruded upon an otherwise perfect melody. Only by aligning myself toward the highest possible Good—the ultimate source of all goodness—could I discern this corruption for what it was. The very act of perceiving the distortion required a measure of purity, a proximity to truth that could only be achieved by aiming at the divine.

This realization underscores the often-repeated religious affirmation: through Christ, everything is possible. The power to identify corruption, to “catch” the flaw in the alignment of Being, exists only because the highest Good makes itself accessible to us. It is the light that illuminates shadows, the standard against which all deviations become visible. Without the transcendent nature of the Good—without Christ as the living embodiment of that Good—we would lack the very tools needed to confront and correct the corruption within us. In this sense, the ability to maintain the purity of truth is itself evidence of its divinity. It reveals a power that is not merely ethical or intellectual but ontological—a force that stands apart, holding firm against the tide of all lesser goods and partial truths. It is the highest, precisely because it does not compete within the world of contingencies. Instead, it defines the axis upon which everything else turns. Only by orienting oneself toward this axis, by surrendering to the source of ultimate goodness, can one hope to transcend corruption and participate fully in the unfolding of truth.

As much as I wanted to avoid it—precisely because I understand how fraught the connotations are in the current cultural climate—the concept of demons offers a compelling framework for understanding this phenomenon. When I caught that thought, that corruption, that deviation, it did not emerge out of nowhere. It wasn’t random or accidental. It bore the marks of something purposeful, a force with direction, if not consciousness—a pattern of deviation actively working against the alignment of truth. The framework of demons provides a kind of cognitive and spiritual grammar for grappling with the fallen nature of human beings. It reflects the deep tension inherent in our existence: within each of us resides an eternal spark of God Himself—the source of Being, the wellspring of Life, and the ultimate Good. Yet, coexisting with that divine spark is an enduring tendency to stray, to distort, to “miss the mark.” The ancient term for sin, hamartia, encapsulates this idea: not merely wrongdoing but falling short of the highest aim, straying from the path. Demons, in this sense, are not necessarily to be understood as external entities lurking in the shadows, though many traditions frame them as such. Instead, they can be seen as manifestations of those forces—both internal and external—that pull us away from the Good. They are the impulses that distort intention, corrupt desire, and lead us into patterns of thought or action that are misaligned with truth.

In recognizing this tension, the framework also offers hope. The very act of catching that corruption, that deviance from truth, signals the presence of something greater within us—the divine spark that discerns and resists distortion. Without the anchoring reality of the highest Good, without God’s light illuminating the path, we would be unable to perceive these deviations at all, let alone confront them. It is this interplay between the divine spark and the forces of distortion that defines the human condition, a perpetual struggle that calls us to aim ever higher, to resist the pull of corruption, and to embody the truth of Being as fully as we can. And of course, it’s easy to miss the mark if you’re not aiming for it in the first place. This is why sin has become the norm in modernity. As a society, we have ceased striving toward the mark altogether. In many ways, we are no longer aiming at anything at all. We are nihilistic—without a center, without a root. People wander through life as if they aren’t truly alive.

To the extent that people have a center today, it is fixed on earthly things—money, pleasure, status. These transient aims form the hollow core of modern existence. They are incapable of sustaining true life, yet they drive people onward in an endless cycle of consumption and dissatisfaction. In this way, many people today are zombies in the truest sense—not truly living but merely existing. This zombification of modernity reflects a spiritual crisis. When we lose sight of the ultimate Good, we forfeit the only aim capable of giving life its fullness and coherence. Without the highest mark to strive for, we fall into a state of spiritual entropy. Our lives become fragmented, dictated by shallow desires rather than by a transcendent purpose. To live in such a way is to exist in a kind of half-death, where the body moves, but the soul remains dormant.

This applied to me for much of my life as well. I wasn’t truly living because I wasn’t aiming at anything. My life lacked a central orientation, a guiding purpose, and without it, I wandered aimlessly, animated but not truly alive. That said, I wouldn’t frame this experience in absolute terms, as if my life prior to a formal “conversion”—a term I hesitate to use and am still not entirely certain applies to me—was devoid of vitality or meaning. It’s more nuanced than that. For the sake of this discussion, let’s assume that such a conversion occurred, beginning with the last session. My soul wasn’t dead; it had simply lost, temporarily, the ability to recognize the center. Yet, even in that state, I was searching. I have always been searching. The search itself—the restless longing for the center, for the highest Good—is evidence of life. It is the inextinguishable spark of the divine within, a yearning to be reoriented toward what truly matters.

This search—the deep and unrelenting drive to uncover meaning, to grasp at the ineffable, to find the source that can anchor existence—is the very essence of this book. It has propelled every moment of reflection, every philosophical inquiry, every attempt to piece together the fragments of my experience into something coherent. Even in moments of despair or confusion, when I felt furthest from the truth, the search persisted. Looking back, I see that my search was never truly aimless, even when it felt like it. It was always drawn, however faintly, toward the center, toward the ultimate reality that I now understand as God. The journey has been far from linear, marked by loops, detours, and moments of profound doubt and utter confusion. Yet, through it all, the longing has remained constant—a compass pointing me toward the source of Truth. This book is not merely an account of that search but a manifestation of it, a way of giving form to the longing that has defined my life.

I wouldn’t have bothered to write anything at all were it not for the burning need to peel back the layers of reality, to penetrate its surface and glimpse what lies beneath. Through considerable effort, study, and no small measure of struggle, I’ve managed to do just that. I’ve drawn back the curtains of existence, exposing its naked truth. And what I found, waiting patiently beyond the veils of distraction, doubt, and distortion, was Christ. This discovery defied every expectation, standing in direct opposition to nearly everything in my life that worked against it—my culture, steeped in secularism and skepticism; my personal history, which often turned me away from faith; and even my own personality, which has always been inclined toward rationalism and resistance to surrender. Yet, despite these barriers, I found Christ—or perhaps more accurately, Christ revealed Himself to me.

It wasn’t an abstract concept or philosophical construct that awaited me at the heart of reality. It was something alive, something undeniably real—something that defied reduction to mere ideas or principles. It was the very center of all Being, the wellspring of truth, and the pure embodiment of the highest Good. This was not an intellectual realization alone, nor a fleeting emotional experience. It was a revelation that struck at the core of existence, encompassing everything I had ever sought or longed for. In finding Christ, I didn’t simply uncover a hidden truth or solve a philosophical riddle; I encountered the foundation of existence itself. It was as though I had been searching for the deepest root, only to find it alive, pulsing with meaning, inviting me into a reality far greater than I could have imagined.

In every conceivable way, I was biased against Him. I was born into a culture where Christianity was not merely dismissed but actively ridiculed—considered the most silly, the most absurd and most implausible of all religions. And I happily aligned myself with that perspective. Religion as a whole was seen as a relic of primitive thought, an indulgence for the weak or the stupid. It wasn’t just that religious answers were considered unsatisfactory; the very questions they sought to address were treated as meaningless. Adding to this cultural background was the framework of my own life. I spent most of my life immersed in scientific education, with no serious religious upbringing to counterbalance the skepticism of my environment. The methods and mindset of science shaped how I thought about the world: evidence, empiricism, rationality. These were the lenses through which I viewed everything. Religion—especially Christianity—seemed antithetical to that worldview, a collection of myths and superstitions utterly irrelevant to modern life. And then, there was my personality. If ever there were traits destined to repel religion, I possessed all of them: stubbornness that clung to certainty even when it faltered, pride that rejected the humility faith demands, and an unrelenting fixation on “rationality” that left no room for anything else.

From a scientific or psychological standpoint, every predictor for Christian belief was stacked against me. Every single one. I was the furthest thing from what you might call “primed” for faith. By all logic, I should have been immune to it, disinterested at best and dismissive at worst. And yet, despite all of this—despite culture, education, and personality—Christ found me. Is this not the very definition of power? To triumph against all odds, to break through even the most impenetrable resistance? What could be more powerful than a force capable of reaching into the depths of disbelief and despair, overturning every obstacle? It is through this lens that the notions of glory—the glory at the heart of Christianity—finally make sense to me. It now resonates with a profound clarity, as if a veil has been lifted. The glory of God is not merely an distant, ambiguous, abstract concept. It is the radiance of truth made manifest, the undeniable brilliance of a power that transforms and redeems. I was asleep. Now I am awake.

Many other religions share this notion of awakening. In fact, my use of it is inspired more by Buddha than by Christ. Just as ‘Christ’ is a title meaning ‘the anointed one,’ ‘Buddha’ is also a title, meaning ‘the awakened one.’ To some extent, this wakefulness results from overcoming deception—a deception that arises naturally from the flesh, with its endless distractions and distortions. But on another level, there must also be a center. If souls are lost until they wake up, what exactly are they waking up to? Buddhism is a tradition for which I hold immense respect and reverence, but one of the core of its teachings is that when one wakes up—when one sheds the delusion of self—what remains is emptiness, pure awareness, and consciousness itself. This state is often described as an enlightenment, a return to the essential nature of existence unclouded by illusion. To some degree, I would consider this a profound form of waking up. Certainly, one’s true identity—the part that transcends the fallen nature—is not tied to the illusions of the ego. In this sense, it can be seen as an overcoming of demons, a release from the forces that keep us bound to deception. But that’s not the whole story.

What’s truly revolutionary about Christianity is that it does not abolish the center. Buddhism, by contrast, focuses on peeling back layer after layer, stripping away every illusion, until one is left with nothing—until the very concept of a center disappears. In the Buddhist framework, the category of the center itself is transcended. This is the essence of nirvana: the extinguishing of all grasping, all clinging, even the subtle attachment to the idea of attaining nirvana itself. True nirvana is achieved only when there is no longer any thought or desire for it. To reach this state, one must transcend all desires and attachments. This insight is undoubtedly correct and profoundly powerful. In doing so, one sheds the bindings of earthly existence. I wouldn’t frame this process in the metaphysical terms traditionally used in Buddhist doctrine, with its belief in reincarnation and the cycle of samsara, but the metaphor still holds remarkable truth. Through this path, one moves closer and closer to the center, peeling away illusion after illusion, relinquishing every layer of self until there is nothing left to shed—not even the desire to shed. And as there is no atman—a self, you then disappear into nothingness. This strikes me as a profoundly spiritual truth, though the word “spiritual” feels inadequate—diluted by overuse, particularly in the modern new-age movement. What I am pointing to here is far deeper, something closer to an ultimate ontological truth: a revelation about the very nature of Being itself.

But the claim of Christianity, as I’ve alluded to before, is radically different: it holds that multiplicity is greater than unity and that agape lies at the very core of reality, triumphing over all else. This central and revolutionary truth transforms the way we approach existence. While Buddhism seeks transcendence through the extinguishing of self and the dissolution of desires, Christianity rejects this path. It makes the fundamental claim that the purpose of life is not to extinguish the center, but to center on something worth living for—a mode of Being that justifies the world and redeems suffering. The Christian vision does not seek an escape into non-existence but rather its opposite. The goal is not to vanish into annihilation, but to move toward life—a true life, overflowing with meaning and purpose. One aligned with the highest ideal and its embodiment.

Which then brings us to the ideal itself, which is Christ. Christ reveals the center through His story and His life. But the question remains: how can you know that Christ is truly the center? How is Christ any different from a demon or an ideology? How can I discern that this force pulling me toward itself isn’t something else entirely—something masquerading as the Good? As I live in the world, I am pulled in a million directions. Every ideology wants for a piece of me. Every demon desires my body for its embodiment. Everything insists on claiming itself as the center. Money wants nothing but money—people live, eat, and work for money. Pleasure wants nothing but pleasure—people live, eat, and work for pleasure. Status wants nothing but status—people live, eat, and work for status. Implicitly or explicitly, each of these centers claims to be ultimate, yet none of them hold. I may be tempted to declare that one particular center is the true center, but how can I be sure? How can I trust that my perception is not clouded by the very forces I seek to escape? It is this tension that always brings me back to Christian theology, no matter where I begin. The center—the true center—announces itself by its capacity to triumph over death. It does not simply promise to hold; it demonstrates its strength through its enduring power, its ability to remain steadfast in the face of annihilation. Christ claims to be the center, not as an abstract idea or a fleeting promise, but through the ultimate act of defeating death itself.

This also ties into the Buddhist notion of the impermanence of things. It is true that everything is fleeting and impermanent—because no center is truly a center. Everything decays eventually, collapsing into cycles of arising and passing away, with nothing enduring beyond its time. This truth seems universal. Unless... the center is something eternal, something that exists beyond the impermanent framework of this world. Christ shatters this assumption, not by denying impermanence, but by transcending it through His divine ontological status. He is not merely part of the cycle but exists outside it, as the unchanging foundation upon which all else rests. Thus, while everything decays and cycles, the center does not—because it is the true center. The true center of the universe. The true center of Being itself. Through Christ, the transient finds its anchor, and the fleeting is drawn into the eternal. Obviously, the center of the universe is not at the cosmological level. The point is that ontology precedes cosmology, or anything else for that matter. This is precisely why Heidegger was so influential for me. His philosophy allowed me to glimpse the world through a lens that modernity, in its relentless fixation on scientific and materialistic paradigms, has largely obscured. By stepping away from a purely empirical worldview and returning to ontology and phenomenology, I found myself rediscovering the foundations of existence itself. This shift was transformative, enabling me to move beyond superficial explanations of the world and toward a deeper understanding of Being. In doing so, I was finally able to uncover the true center—true enlightenment—not as a theoretical abstraction, but as an intimate, ontological reality.

Not an escape from the world, but a striving toward the very essence of the world. It is not about fleeing from Being into the void of Non-Being but precisely the opposite—a movement from the shadow of Non-Being, as dead or lost souls, toward the fullness of Being. It is a journey of awakening, a transformation into Beings that are truly alive, fully aware, and revolving around the center that gives all existence its meaning and purpose. This is not just any center. It is not one shaped by chaotic forces, driven by demonic impulses, or distorted by the shallow materialistic pursuits of status, wealth, and power. Instead, it is the true center, the one that transcends all worldly distractions because it is the center from which everything originates. It is the ground of Being itself—the source of all reality, order, and coherence, standing at the very beginning and sustaining everything that exists. It is the Alpha and the Omega. Only by aligning ourselves with this ultimate center can we truly find our place in the world and become what we were meant to be.

It’s worth noting that when I talk about enlightenment, I hope it’s incredibly obvious that I’m not enlightened. To some degree, what I’m claiming is precisely that enlightenment involves recognizing that you are not enlightened. Enlightenment means something else entirely, something beyond the typical notions of knowledge or personal achievement. In fact, I would argue that the moment one assumes they are enlightened is the very moment they reveal they are not. I am enlightened only in the very narrow and limited sense that I understand the proposition of Christ—that I have been offered a glimpse of a truth far greater than myself. But even with this understanding, I remain a deeply flawed, ignorant human being, no better or worse than anyone else. My position is not one of superiority, as if I’ve reached some lofty spiritual height. Instead, it’s a humble admission of my continued imperfection. When I speak about enlightenment, it’s not from a place of claiming to have attained it. Rather, it’s an attempt to describe the act itself—the quest and its meaning. This perspective is not about personal transformation alone but also about understanding enlightenment as a universal pursuit, perhaps framed through a cognitive or anthropological lens. It’s an effort to articulate what it means to strive toward that which we can never fully grasp, while remaining aware of our own fallibility along the way.

It’s incredible how often people fail to engage with these deeper questions. For instance, my partner jokingly asked me, in my so-called “enlightened” state, with supposed access to “God,” if I knew the answer to which house we should buy, since we’re looking to settle down and start a family. On the surface, it was a playful comment, lighthearted and mundane. But what she doesn’t realize—what most of us fail to see—is that within that seemingly simple, everyday question lies the very essence of all questions: What should I do? What is the center of my decision-making, my priorities, my life? That question alone—what should I do?—is one of such profound weight that it could, and arguably should, keep you up at night for a very long time. It’s the question that anchors every decision, every value, every path we take. But the more you sit with it, the more the question unfolds into further complexity: How can I know that this center I’ve chosen is the true center? How can I be sure that what I perceive as “knowing” is valid? How do I validate the very process of validation? Each layer of questioning exposes an even deeper uncertainty, revealing that no question is ever as benign as it seems. All questions, no matter how trivial they may initially appear, are ultimately religious questions. They are religious because they force us to confront the fundamental structures of meaning and value—what we hold sacred, what we prioritize, and how we navigate the vast uncertainties of life. It is the puzzle of puzzles, the question of questions: what is the center? And more importantly, how do we ensure that the center we revolve around is the true one?

Because no matter what angle of life one examines, it always requires both a framework and a goal. Philosophically, this immediately begs the deeper question: how valid are that framework and goal? What criteria can we use to determine their legitimacy, and how do we know they align with something true or meaningful? The fact that most people don’t even stop to consider this question is a striking indicator of how intellectually stagnant our culture has become—a culture with little to no philosophical interest. It drifts along, oblivious to the very foundations that shape its existence. There is no question more fundamental than this because it underpins and formulates all others. Without interrogating the validity of our framework and goal, everything else we ask remains shallow, disconnected from the deeper truths that give life its meaning.

I’ve made my case for why I believe Christianity, in particular, takes precedence. This belief is not superficial or casually adopted; it is something I hold to the very core of my Being. At the same time, I fully recognize and respect that others may view it differently, especially when their perspectives are grounded in thoughtful study, contemplation, and lived experience. For instance, my rejection of Buddhism is not an uninformed dismissal based on surface-level understanding. I haven’t turned away from it after reading a pamphlet or hearing a few teachings. I’ve engaged deeply with Buddhist thought, having read many books on its philosophy and practices. Meditation has been an integral part of my life through various periods. My “rejection” from Buddhism as the ultimate center, is not born of ignorance or lack of respect; it is precisely because I see something uniquely and profoundly true in Christianity. Despite the wisdom and insights I’ve gained from Buddhism, Christianity offers a vision that resonates with a deeper part of me—something that feels unparalleled in its truth and transformative power. This line of argument isn’t limited to Buddhism; it applies to all religions. However, I’m focusing on Buddhism because, after Christianity, it’s the religion that has attracted me the most, and therefore, the one I’ve engaged with the most as well.

Granted, there are many aspects of Buddhism that I don’t fully understand—or even know about. That’s an inherent truth, and one that I wish weren’t the case. But my time on earth is finite, and the pursuit of truth requires balancing depth with breadth. There isn’t just one thing to study or one field to master. To truly seek the truth, one must strive for a holistic understanding of the world at large. This means not only studying Buddhism but also exploring the other major religions, each of which offers unique insights into the nature of existence. Moreover, these studies cannot exist in isolation. They must be complemented by an understanding of psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, history, and other disciplines that illuminate different facets of human experience and reality itself. This is precisely the approach I have tried to take with my life. I’ve read hundreds of books across a wide range of fields, continually seeking to connect and integrate ideas. I hold a degree in psychology and philosophy, and I pursued a master’s in neuroscience to deepen my understanding of the mind. Through all of this I’ve worked to build a well-rounded view of the world—one that reflects the complexity and interconnectedness of the truth I seek.

But at some point, you have to make a judgment. You can’t study forever. There will always be another theological nuance to explore, another ancient text or new translation to read, and countless interpretations to consider. The quest for knowledge is endless by its very nature, and while that pursuit is noble, it cannot go on indefinitely without resolution. At some point, you must stop, look back at your life and everything you’ve studied, and decide. This isn’t to suggest that I feel pressured to choose something simply because time is passing or because I am growing older—that would be a reasonable, but ultimately false, interpretation. Instead, what I’ve experienced is an intuition, arising from the very depths of my soul, that Christianity is true. This intuition has persisted even in moments when I couldn’t fully articulate why or felt uncertain about certain aspects of the faith. There is an undeniable discomfort in making such a declaration—that this is the correct path—especially without having exhausted the depth of every other possible path. Yet, the discomfort is not a sign of doubt but of humility, of recognizing that no human decision is ever made with perfect knowledge. This is not about feeling trapped or compelled to pick a religion. It’s about coming to terms with the inevitability of making an existential judgment and finding peace in that decision knowing that one’s knowledge is always insufficient. It means acknowledging that such a judgment, while imperfect, is necessary, and trusting that the intuition guiding me is grounded in something real and profound.

I’ve done my best to approach this decision as rationally and thoughtfully as possible, in the fullest sense of what actual rationality entails. Ever since I was 18, I’ve been striving to uncover the mysteries of this world. That journey began slowly, through reading philosophy, and over a decade later, it has taken me deeper than I ever expected. In fact, this pursuit of understanding is what initially sparked my interest in psychedelics—a tool that allowed me explore paths I would have never encountered otherwise. Before psychedelics, I had what I considered a perfectly coherent worldview, one firmly rooted in the normal, naive assumptions of materialism. It seemed rational, stable, and sufficient—a framework that comfortably aligned with the scientific outlook most of modern society takes for granted. But when I encountered psychedelics, I was fortunate enough to recognize that they were revealing something extraordinary. They began to uncover hidden aspects of reality that I hadn’t even known existed, let alone considered. Even before trying them or having any detailed knowledge of their effects, I had an intuitive sense that they held the potential to illuminate truths that lay beyond my current understanding. That intuition set me on a path I’ve been pursuing ever since.

However, it’s not as though I’ve been casually taking LSD in isolation, hoping it might magically reveal the ultimate truth of the world. My use of psychedelics has always been paired with an attitude of profound seriousness and respect. Every experience has been accompanied by rigorous study, not just of religions but of the very structure of consciousness and the fundamental nature of thought itself. I’ve approached these experiences as part of a broader, interdisciplinary exploration, combining insights from philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and theology. It is this synthesis—this relentless pursuit of understanding—that has brought me to where I stand today. Every step of this journey, from my initial foray into psychedelics to the years of contemplation and study that followed, has led me to this place. All of it, in one way or another, has led me to Christ.

I don’t know what else to say if nothing I’ve written in this book has conveyed the truth of Christianity. I don’t mean it in the fullest, most doctrinal sense—the kind of knowing that Christ is the Son of God with absolute theological precision. Rather, I mean it in the softest, simplest way possible: the feeling of Christianity pulling you in, just as it has pulled me. For instance, I’ve felt this pull for the past six or seven years, a quiet yet persistent draw toward something I couldn’t entirely articulate. And yet, it is only within this last year that I’ve begun to understand, even just a little, why Christianity is true—not just in an intellectual sense, but at the deepest levels of reality. You don’t need to understand everything; I certainly don’t. But I do understand enough to recognize the truth at its core, the truth that allows me to proclaim it without hesitation. All you need to do is feel its pull. That’s all. God is stretching His hand out to you, just as He stretched it out to me. You don’t need perfect clarity, or perfect faith, or perfect anything. You just have to take His hand. The rest will follow.

Christianity cannot be preached through purely rational means. It defies the kind of explanation that fits neatly into syllogisms or airtight proofs. I’m not trying to make you a “believer” as I lay out my thoughts, nor am I presenting them as formal arguments, as if I were submitting a scientific paper for peer review. I’m fully aware of their gaps, their ambiguities, and the ways they resist systematic analysis. This is not about offering a watertight argument of premises and conclusions. Instead, what I’m doing is more akin to painting in written form. It’s a painting that is mystical in nature, one deeply rooted in my life experience and the truths I’ve glimpsed along the way. Every stroke reflects my journey, my struggles, and the moments of clarity I’ve been blessed to encounter. All I’m trying to do is share my reflections in the hope that they ignite a spark of understanding—just a glimpse into what my worldview is like. Once you’ve caught that glimpse, the rest is no longer in my hands. It’s up to you. You must walk the path yourself, just as I had to. But walking that path requires something rare: a willingness to uncover the deepest truths of this world, stripped of preconceptions and freed from the weight of prior assumptions. It demands courage to face unsettling truths, humility to admit what you don’t know, and a readiness to see the world not as you expect it to be, but as it truly is. That’s where the journey begins, and it is also where it will ultimately lead you—if you allow it.

It’s not an easy path. It requires an immense amount of effort: reading, questioning, and striving to understand. It calls for a deep engagement with philosophy, theology, cognitive science, and even neuroscience, because uncovering truth means addressing not just what you believe, but why you believe it. Often, this effort isn’t even about understanding Christianity directly; it’s about breaking free from the illusioned, mechanistic worldview you’ve inherited from the modern world—a perspective that narrows reality to only what is material and measurable.

Ultimately, though, it’s up to you: do you want to remain in a state of perpetual sleep, lulled by the comfort of convention and unquestioned assumptions? Or do you want to be truly awake, to see things as they are, no matter how unsettling or challenging that might be? Nothing and no one can take that step of awakening for you. It is a choice that only you can make. But if you genuinely desire the truth and pursue it with earnestness and sincerity, the path will reveal itself. And in time, if you keep walking, you will eventually find it. It took me many, many thousands of hours. But I didn’t start from a place of clarity or understanding. I started from a very naive, very limited worldview, one far worse than average. Because of that, the path I had to walk was long, difficult, and often deeply frustrating. Chances are, your journey won’t be as arduous. But even if it were that difficult, it would still be worth every step. For millennia, countless people have dedicated their entire lives to searching for the answer—striving to uncover the ultimate truth of existence. Every single culture in human history has developed some notion of Enlightenment, some vision of awakening. And within each of these cultures, there have been individuals who gave everything they had, relentlessly pursuing, to the best of their ability, the Truth. This enduring quest for meaning—the willingness to sacrifice comfort, certainty, and ease in order to glimpse something greater—speaks to the value of the journey itself. No matter how long or difficult the path may be, the pursuit of Truth remains one of the most profound endeavors a human being can undertake.

Many, unfortunately, have spent their entire lives searching without ever finding the answer. Yet their efforts were not in vain. They tried everything within their power, dedicating themselves to the quest for understanding because the answer they sought was worth any sacrifice. It is the answer that lies at the heart of existence itself—the divine nectar of truth. Throughout history, countless yogis, monks, mystics, and seekers have gone to unimaginable lengths in their pursuit of awakening. They have explored every form of theology, explored every conceivable practice of asceticism, and tested the limits of human endurance—all for the smallest chance of tasting even a drop from the sacred nectar of ultimate truth. Some fasted to the brink of death, their bodies reduced to emaciated shells in their quest to transcendence. Others sought isolation in the most extreme conditions, meditating for years in remote caves, their bodies worn-out by freezing winds in the deep winter, or likewise the extreme heat of the desert. There are stories of monks reciting prayers for days on end without sleep, until their voices failed, or walking thousands of miles on foot to reach sacred sites.

Many have died in these attempts—succumbing to malnutrition, exposure, or sheer exhaustion. They considered such risks worth taking, for the chance to draw closer to the divine. Their lives, even if cut short, were acts of ultimate devotion, driven by a singular conviction: that awakening is not merely a secondary goal but the very purpose of life itself. So, when I ask you to engage in study and deeper reflection, to take up the challenge of seeking truth, it pales in comparison to the sacrifices others have made. In the broader context, it is hardly a request at all. It is an invitation to join the great tradition of those who dared to pursue the highest calling, to seek that which is greater than oneself, and to embrace the path toward becoming truly awake.

Granted, you don’t necessarily have to undergo extensive study or seek mystical states to recognize the truth of Christianity. One of the profound beauties of Christianity is its accessibility—it is meant to be understood and embraced by the layman. It is not exclusively a religion for philosophers, theologians, or mystics; its message resonates with simplicity as much as it does with depth. The invitation to faith and the call to follow Christ is open to everyone, regardless of their intellectual pursuits or spiritual experiences. Yet, because of the deeply materialistic culture we live in, it has become increasingly difficult for people to see this truth in its current form. Modernity’s obsession with what is tangible, measurable, and scientifically verifiable has obscured the spiritual dimension of reality. This worldview reduces existence to atoms and mechanisms, leaving little room for the sacred, the transcendent, or the divine. In such a culture, the simplicity of Christianity—the profound truths it offers through love, grace, and faith—often goes unnoticed or is dismissed outright. The modern mind struggles to grasp what cannot be dissected, categorized, or explained through purely rational means. As a result, many find it harder to recognize Christianity for what it truly is: not just a system of beliefs, but the ultimate framework for understanding existence, one that speaks to the deepest needs and questions of the human soul. Still, many people see the truth of Christianity with zero intellectual work and without undergoing mystical experiences. And bless them for it. That is the true meaning of the words: “You believe because you have seen me. Blessed are those who believe without seeing me.” This is not a call to suppress rational thought or embrace something magical in a naive or blind sense. Instead, it is about being spiritually alive enough to recognize the truth, even if you can’t fully understand how it can be so. In much the same way, a person can recognize the reality of gravity without understanding the formulas or the underlying principles to grasp that gravity exists and governs their world. Similarly, those who see the truth of Christianity without extensive study or profound experiences possess a kind of spiritual clarity, a gift that allows them to embrace what others might struggle to comprehend.

But not everyone is blessed with such clarity. I, for one, was as far from that situation as one could possibly be. Given my circumstances—my personality, my culture, my environment, and countless other factors—I was utterly lost. My understanding of the world was narrow and fractured, and the light of truth was obscured from my view. My only salvation was an insatiable drive toward truth. That hunger became the guiding force of my life. It first led me to psychology, as I sought to understand the human mind and its depths. Psychology, in turn, opened the door to philosophy, where I began to wrestle with the larger questions of existence. Philosophy led me to religion, and it was through religion that I finally encountered Christianity.

In your case, the path may differ. You might require a deeper engagement with reading or even mystical experiences to begin grasping the profound depths of this world, or you might not. To some degree, it might seem unconventional—perhaps even strange—to suggest psychedelics as part of that journey. I fully acknowledge that this is far from the norm within Christianity, and I am well aware that many believers, priests and monks would strongly oppose such a suggestion, dismissing it outright as heretical. I understand their perspective, and I respect the concerns that drive their opposition. Yet, I must respectfully disagree. My own journey has shown me that psychedelics, when approached with seriousness and reverence, can serve as a tool to unveil truths otherwise hidden. While they are not the only way, and certainly not for everyone, they were a key part of my awakening—a catalyst that shattered my preconceptions and opened my heart to the divine.

I am most certainly not saying that Christianity can only be discovered through psychedelics or mystical states more broadly. Far from it. What I am saying is that psychedelics can serve as a powerful tool for breaking through naive, inherited worldviews and opening the door to deeper inquiry. They can be a catalyst for starting the chase, so to speak—an invitation to follow the white rabbit. But that investigation, that chase, must ultimately be pursued in sobriety. Psychedelics can open the door, but they cannot walk the path for you. You can’t be intoxicated all the time, nor should you be.

I would argue that the antagonism toward psychedelics within Christianity is largely a historical, political and cultural artifact, a bias shaped by particular societal forces rather than theological or moral necessity. Yet, this perspective is challenged by how psychedelics have been used throughout human history, including in deeply religious contexts. Across countless cultures, they have been integrated into rituals and spiritual practices, serving as tools for accessing states of consciousness that foster insight and transformation. I wish we lived in a society where psychedelics weren’t so spiritually useful—where their utility as a bridge to deeper truths wasn’t so potent. In a world less dominated by materialism and capitalism, where people were more educated and spiritually attuned, these truths would likely be far more intelligible on their own. In such a world, the need for psychedelics as a tool to pierce through the veil might diminish entirely. But alas, we do not live in such a world. The society we inhabit is profoundly disconnected from the sacred, entrenched in a worldview that reduces reality to what is measurable, commodifiable, and profitable. In this context, psychedelics offer a means of glimpsing something greater—something beyond the shallow confines of materialism. They can serve as a spark, igniting the desire to uncover the deeper truths of existence. But it is ultimately up to each individual to carry that flame forward, in sobriety, with clarity, and with an earnest heart.

Most people have little to no education in psychology, philosophy, religion, history, or anything else outside their specific domain of expertise—the knowledge they require for their jobs. And those jobs, for the majority, are purely a means of survival, a way to earn a living and keep life moving. We live in a society that does not encourage thinking beyond these necessities. It is not a religious culture, and it’s not even a philosophical culture. Instead, it is a culture of consumption—a culture of death, where meaning is traded for distractions, and people wander aimlessly, unchained from anything greater than themselves. This isn’t something I, or anyone else, can change in any meaningful way. The structures are too deeply embedded. The best I can do is point out the reality we’re trapped in and offer reflections for those who are willing to see it. Given this, if people want to use any means they find necessary to pursue their goal of discovering the truth, they should—provided, of course, that it doesn’t cause harm to themselves or others. And contrary to the fears and stigmas surrounding them, psychedelics, when used responsibly, do not cause such harm.

To reiterate one last time: I’m not saying that you need psychedelics to uncover the truth. Far from it. I’m simply saying that they are an acceptable tool—a means that some may choose to incorporate into their journey. You might decide never to use them, and that’s perfectly fine. In fact, more power to you if you can pursue the depths of truth without them. That said, psychedelics can be profoundly useful, though their utility often comes with challenges. They are not easy tools to wield, and their power lies in their ability to expose what often remains hidden—the raw and unfiltered depths of your own soul. They can be deeply frightening in the very same of that they are deeply transformative. The decision to use them, or not, is entirely yours. But if you’re brave enough to venture into those depths, you may find yourself facing truths that are both frightening and awe-inspiring, the kind of truths that can fundamentally reshape your understanding of yourself and the world.

As stated, my goal isn’t to convince you or to impose my beliefs upon you. Instead, it is simply to share my experience—to show you a different worldview and a different way of thinking. Through this, I hope to provide you with a perspective that might allow you to glimpse something you hadn’t seen before. That glimpse, however fleeting, is enough to spark something within you. Truth has a way of calling out to those who encounter it, even briefly. It is a call that resonates deeply, a quiet but persistent invitation that demands attention. Once you’ve seen even a fragment of the truth, it begins to reveal itself in ways you cannot ignore. And from there, it is no longer about persuasion or argument; it becomes a personal journey, one that you feel compelled to undertake, drawn by the call of truth itself.

No human being truly wants to remain asleep when they could be awake. It is in our very nature, as beings capable of reflection and wonder, that once we catch even the tiniest glimpse of the truth, we are compelled to seek it further. That initial glimmer ignites something deep within us—a longing to pursue it, to follow it, no matter how elusive it might seem. We begin chasing the white rabbit, letting it lead us down paths we could never have imagined. You may feel afraid to chase it, as I once was. The path ahead can appear daunting, filled with uncertainty and challenges that threaten the comfort of what you know. But eventually, if you allow that spark to grow, you will find the courage to take the first steps. And with time, you will gather the bravery to keep going, no matter how difficult the journey becomes. The real problem lies with those whose lives are so confused and lost that they don’t see anything at all—not even the faintest hint of light to guide them. They wander in darkness, unaware of what they are missing, unable to recognize the call that truth is always making.

My goal is not to force truth upon you or dictate where your path should lead. It is far simpler than that: my goal is to help clear the dirt from your eyes so that you can see for yourself. The light is already shining, always has been. All you need is the clarity to perceive it and the courage to follow where it leads. My deepest hope is to bring at least a single soul closer to salvation. Not salvation as a childish fantasy of living eternally in the sky, but salvation as true personal transformation—true enlightenment. This enlightenment is not the abolition of a center, as some philosophies might suggest, but a redirection toward the one true center, the foundation of all that is.

If my words fail to fully resonate with you right now, that’s OK. I am just a man. I have limitations, and my words, no matter how honest and deeply felt, are nevertheless flawed and mortal. But I trust that truth has a way of making itself known, and my hope is that something here will be a spark—perhaps a small one—that might grow in time. If not, then perhaps a more gifted writer, or someone whose experiences align more closely with your own—will eventually show you the light. Just please, whatever you do, don’t stop seeking it. I don’t care if you think Christianity is false, or even if you dismiss all religions as deeply flawed and useless superstitious oppressive systems. At the very least, aim for the highest thing you can conceive. Fix your gaze on the summit, no matter how distant, and let that vision guide you forward. For if you commit yourself to that pursuit—to striving for the highest good, the ultimate truth—then, in time, it will begin to reveal itself to you. The shadows will retreat. And the light will grow ever brighter, until it consumes you, transforming you from within. And in that moment, you shall be awake. Fully, utterly, gloriously awake.

Previous: Volume 4 Chapter 2: Love as Ontology

Next: Afterword