Posterazzi Where Heaven and Earth Meet (1888)

Posterazzi Where Heaven and Earth Meet (1888)

“Philosophical activity is fully real only at the summits of personal philosophizing, while objectivized philosophical thought is a preparation for, and a recollection of, it.”

-Karl Jaspers

“Thinking only begins at the point where we have come to know that Reason, glorified for centuries, is the most obstinate adversary of thinking.”

-Martin Heidegger

Volume 3

Chapter 3: Searching for the Real

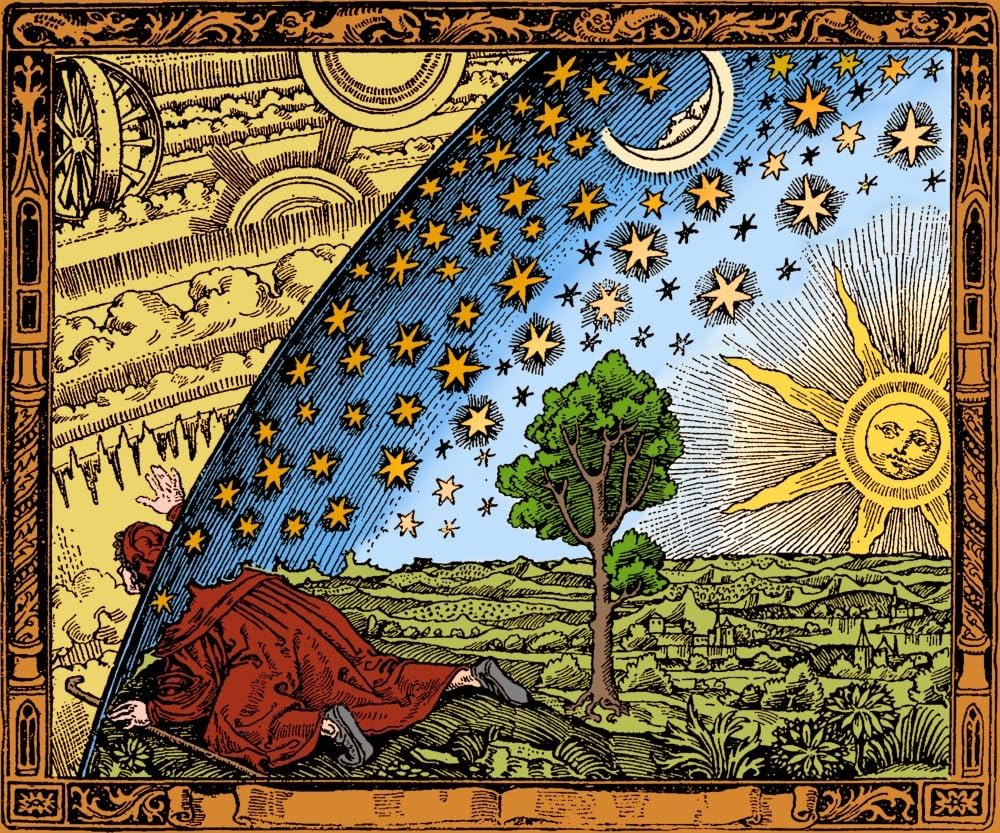

I wanted to focus this session on the subject of love, a topic that has increasingly occupied my thoughts as I deepen my current romantic relationship. When I am away from my partner, I often find myself pondering the essence of love—what it truly is at its core. I’ve conjured metaphors in my mind, imagining love as something real yet obscured by layers of illusion or misunderstanding. This idea resonated deeply during my last LSD session, influenced by a movie in which discerning the “true” was a central theme. In this analogy, love is like a precious stone covered in dirt, waiting to be cleansed to reveal its innate purity. The process of uncovering this truth, this aletheia—the Greek term for an unfolding or revealing of truth—is a progression, much like the journey of love itself. In exploring this theme, two major metaphoric symbols have emerged in my reflections. One is the idea of a center, something that we draw nearer to or move farther from. The other is a mountain, something we climb higher upon or descend from. I’ve referenced both symbols in various writings, and while they describe the same concept, each seems better suited to particular contexts. Both symbolize a higher or deeper value—either at the peak of the mountain or at the core of the center.

When discussing love in a Christian context, agape represents the highest and purest form of love, akin to a diamond or ruby—precious, enduring, and transcendent. Yet agape is difficult to grasp or experience directly. Instead, we more often encounter eros, a more immediate, consuming form of love. This distinction is essential because the word “love” encompasses a wide range of meanings and manifestations. For example, parents love their child so deeply that they would willingly give their life for them. Yet, someone might also love playing video games. Clearly, these are not the same kind of love, yet we use the same term for both.

At its core, consciousness itself involves caring about specific things. Martin Heidegger captures this idea in his concept of Dasein—human existence as fundamentally tied to care. This is what distinguishes humans from mere instruments like thermometers. While both humans and thermometers process information and respond dynamically to changes in the environment, I have the capacity to care about the information I process. This care, however, is not abstract or detached; it is rooted in biological imperatives. For any species to endure, it must first survive, and for survival, it must care about certain essentials. From this basic necessity of care, a hierarchy of values emerges, each tied to our survival needs. For instance, because our bodies require nourishment, we naturally crave food. This drive to fulfill what we need for survival is the essence of eros—a consuming, desirous form of love. Eros is not limited to physical hunger; it extends to all forms of yearning for what sustains or completes us. Agape, by contrast, transcends this biological drive. It represents a higher, unconditional love that is not rooted in desire or consumption but in selflessness and giving. Yet, because eros is closer to our immediate experience, it often serves as the entry point or stepping stone to understanding and embodying agape. The progression from eros to agape mirrors the metaphor of cleansing the stone—gradually revealing the deeper, purer truth of love.

Eros often manifests as sexual desire, which, while closely associated with love, is not considered a fundamental component of true love. Beyond physical necessities, emotional needs play a crucial role in relationships. However, eros should not be narrowly defined as mere sexual attraction. The term derives from eran, meaning “to desire,” and encompasses the broader emotional fulfillments we seek in a partner: comfort, security, validation, and more. All these desires, which we aim to “consume” to satisfy our needs, fall under the domain of eros. Yet none of these desires fully captures the essence of true love—agape. Agape transcends any form of need or desire. Often described as “pure” love (here I find myself once again caught in the constraints of symbolic language), agape is perhaps best exemplified by the metaphor of parenting. Scriptural narratives frequently present God as a parental figure, embodying a form of love that contrasts sharply with eros. Unlike eros, children do not satisfy physical needs—in fact, they often amplify them. Parenting can strain resources, disrupt sleep, and bring significant challenges to physical and emotional well-being. While children may occasionally meet emotional needs, this is not the norm, especially in their younger years. Infants and young children can be irrational, demanding, ungrateful, and exhausting—the very antithesis of eros, which seeks fulfillment. Yet, despite these challenges, love for one’s child often persists, unconditioned by any contribution they might make.

This form of love is selfless, enduring, and unconditional. As Gautama Buddha claimed, the love a mother feels for her child should be extended to all beings, a universal love that transcends personal desires or needs. Agape, then, is not about what one receives but about what one gives—a love that exists independently of any return. This duality of love, with its superficial and profound layers, feels almost intuitive. But what preoccupies my mind is this: why does it feel intuitive? Why does the distinction between eros and agape seem so fundamental, as though it reveals an underlying truth about existence itself? Once again, we confront the aletheia of truth, climbing higher and higher on the metaphorical mountain. But what supports this mountain? What constructs the very concept of value that shapes our understanding of love? Who determines that agape is the deepest form of love, superior to eros? How can we definitively locate the center, the core truth of love? It seems that the concept of value itself is precarious, vulnerable to infinite interpretations and possibilities. Each perspective might be as valid as the next, fracturing into countless meanings. And yet, despite this potential for disintegration, we continue to intuitively sense that agape represents a higher, purer ideal. The question, then, is not only about understanding the duality of love but also about grappling with the very foundations that support our sense of meaning, truth, and value.

In recent months, I have been deeply wrestling with the intertwined problems of love and realness. These thoughts have taken on a new intensity since my mother was diagnosed with cancer last month. The news has devastated me for several reasons, but one of the most profound is the sheer pity I feel for her. She is such a good person and, tragically, has not had the most fulfilling life. This diagnosis felt like an unjust blow—a final insult to someone who has already endured so much and received so little in return. Her diagnosis also provoked an unexpected surge of anger—anger at reality itself. How could something like this happen to my mother, someone who has given so much? This question of fairness, though fundamentally unanswerable, lingers in my mind, amplifying my grief.

When I first heard the news, I found myself questioning my own reactions. The idea of your mother getting cancer is universally recognized as one of life’s most dreaded trials. But I began to worry: Was I as upset and disturbed as I should be? How much did I truly care about my mother? What was the capacity of my own love? This introspection turned inward, forcing me to confront a long-standing fear: that I might not be “human” enough, that my emotions were somehow hollow or inauthentic. Was I grieving because I truly felt grief, or because I knew that was the expected response? This brought me back to the central question of what is “real.” Was my grief real? Were my emotions authentic? Despite these doubts, I believe that I do care deeply—that I am capable of love. But this capacity feels like a small, precious stone buried under a mountain of dirt. That is agape, and that, I believe with conviction, is real. I may not fully understand the epistemological foundation of this belief, but I am willing to stake everything on it.

The issue of realness in love has been occupying my thoughts more frequently, particularly in the context of my romantic relationship. I often find myself questioning: Do I truly love my partner, beyond the superficial fulfillment of needs? Many people claim to love their partners, and I do too, but few deeply examine what love truly means or whether they are meeting that standard. Much like with my mother’s situation, I’ve recognized that many of my feelings in this relationship are rooted in eros. Yet, I also believe there is a spark of agape, no matter how small, and that it can be cultivated with deliberate effort. In the Christian sense, love is not merely an emotion but an act of will, something actively practiced. It is like ascending a mountain, striving to reach the ultimate center. This idea ties back to my earlier reflections on the power of “willing” something into existence—the very act of seeking love helps manifest it in the world. For example, in Blade Runner, the concept of love emerges from the will to love. The question then arises: Why do we believe in agape at all? Why do we imagine this “precious stone” of selfless love? Does it truly exist, or is the world confined to eros? Instinctively, most of us know that love is more than the fulfillment of physical, sexual, or emotional needs. When we truly experience love, we catch a glimpse of its deeper reality—a reality that transcends biological drives. Within each of us, there is a “divine spark” that allows us to recognize agape and bring it into existence.

Eros, however, is undeniable. It often masks or obscures agape, but that isn’t inherently wrong. Eros reflects our fundamental needs, which are a vital part of existence. The goal is not to condemn eros but to cultivate agape as much as possible. Unlike Gnosticism, which viewed the earthly and physical as inherently corrupt and the spiritual as pure, Christianity does not see the body or earthly desires as evil. Evil originates in the mind and is expressed through the body, but the body itself is not the problem. This perspective shifts the focus from rejecting eros to enhancing agape. Salvation, in this context, is not about destroying our earthly desires or achieving an ascetic detachment from the world. Rather, it is about actively cultivating agape—removing as much of the dirt as possible from the precious stone of love and climbing as high as we can toward the summit of selflessness and truth.

It’s striking how the question of what is “real” applies to so many aspects of life. Lately, I’ve felt an increased capacity for emotion—a sense of becoming “more human.” This deepened sensitivity seems intrinsically tied to love and aesthetics, both of which feel like glimpses of divinity that we can occasionally access. Motivated by this awakening, I turned to music as a pathway to deeper understanding. After watching a particularly poignant movie, I immersed myself in Mischa Maisky’s performance of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major. It’s one of my favorite pieces, and I resolved to listen deeply, allowing it to resonate within my soul. As I listened, I began to cry. The music’s beauty was overwhelming. Yet even in that moment, I found myself questioning the authenticity of my tears. Were they truly a response to the music’s beauty, or were they fulfilling an unconscious need for emotional connection? Was I seeking an overwhelming experience to “validate” my existential need to feel human? The tears felt real, but were they truly real? I realize that my skepticism may seem excessive, but it’s not unfounded. You and I both know that such layers of reality exist. We often take for granted the superficial layer of experience, believing a deeper, more “real” layer underpins it. But where do these layers intersect? How can we discern what is truly fake from what is truly real?

Love, for instance, is an intricate interplay of these layers. Love for a partner or a parent undoubtedly involves eros, the desire-driven, consuming aspect of connection. Even if we acknowledge the presence of agape—the selfless, transcendent form of love—how can we pinpoint where one ends and the other begins? Are these distinctions ever truly clear? This uncertainty brings us to a deeper question: how much of our experience is shaped by self-deception? Do we unconsciously cling to illusions, confusing the non-real for the real in our attempts to stay connected to what we perceive as meaningful? Perhaps the challenge is not to eliminate this ambiguity but to recognize it and navigate it as part of what it means to be human.

Shortly after my mom’s diagnosis and my return home to stay with her, I experienced an unexpected and profound sense of connectedness—not just with her, but with everyone and, in a way, with the world itself. Paradoxically, amidst the sadness, I felt happier: more sociable, patient, resilient, and kind. It was as if Christ’s spirit was moving through me, acting within me. I understand how this might sound to atheists, but I don’t necessarily mean anything supernatural. Rather, it felt like living in the spirit of what Christ symbolizes—His ethic, His way of being.

This is a large part of what Christianity offers as an inheritance: the idea that history itself is divided by Christ, the ultimate kairos—a concept from ancient Greek meaning the right, critical, or opportune moment—which in Christian theology denotes a transformative moment influenced by Christ’s presence in history. This notion is particularly relevant in discussions about life-changing personal experiences or decisions that align with divine timing or spiritual awakening. Through Christ, it is possible to experience metanoia, the transformative shift symbolized by being “born again.” It is such a fundamental shift in your being that it feels as if you were a completely new person, a better person. Your own personal kairos emerges from embodying agape rather than from a solely historical one. This change is so fundamental to your being that it is as though you become an entirely new person—a better person. It is your own personal kairos, rather than a historical one, born from embodying agape.

I felt this transformation to a small degree—not with the intensity often depicted in theological discussions, but enough to catch a glimpse of what it might mean. It was just a hint, but that hint was enough to remind me of the path I should take. The depressing part is that I can already feel this sense fading. There’s a painful inevitability to the idea that I will return to my old self, with all its flaws and shortcomings. But having experienced even a glimpse of this transformation gives me hope. I know that it is real, that it is possible, and that it is worth striving for. Experiencing that state of mind allowed me, even amidst the chaos of my life—being separated from my partner and my mother confronting death—to find moments of peace. In those moments, I felt connected to something “real,” as if I were able to clean some of the dirt off and glimpse a purer reality.

While I was in this glowy state, an incident at the gym challenged my sense of calm and connection. After being done with my session and using the restroom, I approached the sinks to wash my hands. A man was shaving at the sink I needed, and I waited nearby, hoping he would notice me and make some space. When it became clear he wasn’t moving, I assumed he hadn’t seen me, so I stepped closer and said something like, “Sorry, just a second.” He didn’t move much, and I unintentionally encroached on his space as I used the sink. Immediately, he began to complain, calling my actions rude. I apologized and tried to explain the situation, but he seemed deeply offended, continuing to voice his frustration. I don’t recall his exact words, but his tone was cutting and condescending. As I packed up after my workout, he kept trying to scold me. Every time I attempted to interject, he interrupted, dismissing me outright. At one point, he made a comment implying that “people like me” were beneath his notice, as if I lacked inherent worth. It became clear that the conversation was futile. Realizing this, I stopped engaging and focused on gathering my things before leaving.

The encounter lingered in my mind, unsettling the “Christian glow” I’d been experiencing. I replayed the situation, questioning whether I had been too forceful in moving into his space. While I acknowledged that I could have been more mindful, I felt his reaction was disproportionately harsh. The incident annoyed me, especially since his tough demeanor—complete with face tattoos and unfriendly body language—made it feel more hostile. It was a stark reminder that no matter how open or connected I might feel, there will always be someone ready to disrupt that peace.

The next day, I was back at the gym, still reflecting on the incident. I mulled over his disproportionate reaction, wondering if something in his life had put him in a bad mood. As I thought this, I noticed him out of the corner of my eye, across the gym. Remembering how unpleasant our last interaction was, I deliberately avoided eye contact, hoping to avoid any confrontation. While I rested between sets, scrolling through my phone, I saw him walking toward me. I braced myself, dreading another clash. But to my surprise, he extended his hand for a handshake. He offered a sincere apology for his behavior the day before, admitting he’d acted poorly. I shook his hand and accepted his apology, adding that I could have been more polite when asking to use the sink. He apologized again and then walked away. This turnaround confirmed that I had initially misjudged him as simply a “bad” person—an error corrected almost instantly by his subsequent apology, a perfect example of what Jung might describe as synchronicity. Reality, which had felt so small and tense during our initial conflict, opened up again through his act of apology. Reflecting on this incident forced me to reconsider my long-standing disdain for ideas like the mind influencing reality—concepts I had firmly rejected since my teenage years. Such notions always seemed incompatible with the immutable laws of nature and fundamentally flawed on a moral level. After all, I couldn’t wish away my mom’s cancer with positive thinking. And yet, this encounter prompted me to reevaluate my skeptical stance, hinting at a more intricate interplay between our perceptions and the external world.

At the time, my understanding of reality was rudimentary. I was deeply entrenched in a rigidly scientific worldview, eager to expose beliefs I deemed foolish or demonstrably false. Looking back, I cringe at the arrogance and oversimplification of my views, but I can also acknowledge their value. Pseudoscience and superstition do real harm, and my commitment to debunking them was not entirely misplaced. However, my approach was overly materialistic and lacked any philosophical depth. While there is undoubtedly an objective reality—something science is uniquely suited to explore—the reality we inhabit is not solely defined by science. By its very nature, science excludes value, yet value is central to the human experience. Our lives are framed by values, forming the very structure of our reality. In this sense, our phenomenological experience is the core of our reality, shaping how we perceive, interpret, and interact with the world. Science, while invaluable, is merely a tool to investigate one dimension of this multifaceted reality. True understanding requires a broader perspective, one that integrates the subjective, value-laden aspects of existence with the objective insights provided by science.

The ideas of positivity—of altering your reality—are not necessarily supernatural. In fact, the tendency to label them as supernatural likely reflects our current bias toward interpreting everything through a materialistic and scientific lens. These ideas are fundamentally about consciousness, about how the world is perceived and framed. That’s what changes, and that’s what’s real. Of course, you can’t break a lock simply by thinking about it, but if your framing of the world shifts, perhaps you discover a way to break that lock. A flash of insight may reframe the situation, revealing a solution you hadn’t previously considered. Certain ideas influence your frame in specific ways, altering how you see the world and how you act within it. That shift in perception becomes your reality. In this context, talking about “objective reality” feels pointless, as we have no direct access to it.

This perspective profoundly shapes how we interpret events. Take my gym incident, for example. Was it mere coincidence? From a purely materialistic viewpoint, it was. I don’t believe any specific agent, such as God, orchestrated the event. And yet, why doesn’t it feel like a mere coincidence? Why does it seem infused with meaning, as though the connection holds significance? The more scientific version of myself would argue that this sensation arises from cognitive biases shaped by evolution—a valid point. However, dismissing these biases as mere errors is itself a bias. These so-called biases are, in fact, mechanisms through which we perceive and interpret reality. They employ heuristics—mental shortcuts—because our knowledge and computational abilities are limited. While helpful, these heuristics sometimes lead to errors, which we categorize as cognitive biases.

The real challenge lies in determining when these mechanisms are functioning effectively. If their purpose is to model objective reality, then their outputs should align with it. But the truth is, we aren’t fundamentally designed for objective reality. While we possess some capacity to create coherent mental models of the physical world for navigation, we also rely on models for understanding complex social and ethical issues—models that don’t align neatly with a materialistic view. These models are not necessarily supernatural, but they highlight the limits of reducing all experience to physical laws. Social and ethical realities operate within layers of meaning and value that cannot be fully explained by materialism. Recognizing this doesn’t diminish the scientific worldview but complements it, allowing us to understand how our perceptions shape the reality we experience.

Suppose I am reading a book on philosophy. Which is more likely: that I enjoy reading, or that I enjoy reading and learning about philosophy? Most people would intuitively choose the latter. However, this is technically incorrect. By definition, the set of people who enjoy reading is broader than the subset of those who enjoy both reading and learning about philosophy. Adding an additional condition to the base variable reduces the probability, yet our cognitive processes often overlook this. This example demonstrates how easily our reasoning can be deceived, especially when dealing with probabilities. The framing of the question usually lists both sets, describing the larger set (enjoying reading) before the smaller one (enjoying reading and learning about philosophy). This sequence subtly implies that the smaller set is more relevant or likely, leading people to select it. The added specificity feels more aligned with the context, even though it is statistically less probable. Now consider a slightly different scenario. Suppose you didn’t know the book was about philosophy but noticed it on the bookshelf of a philosophy undergraduate, next to a sculpture of Rodin’s The Thinker. In this case, you might reasonably infer that the book involves philosophy. The conjunction of these clues—the bookshelf’s owner and the sculpture—provides stronger evidence together than either would alone. This inference reflects a natural human tendency to combine related variables to increase relevance and accuracy. This isn’t necessarily a flaw in probabilistic thinking; rather, it reveals a flaw in how certain problems are framed. When a question is constructed to highlight additional conditions as though they add relevance, it leads us to make assumptions that might technically be incorrect—but in most everyday contexts, these assumptions would actually serve us well. The broader issue lies in how we view cognitive biases. They are often criticized for leading to errors in analytical reasoning, but they are less problematic—and often highly adaptive—when applied in social contexts. This makes sense if we consider that rationality likely evolved to help us navigate social environments rather than to solve abstract mathematical problems.

The problem is further exacerbated by how we use language. Language is often treated as a tool for conveying strictly logical information, like the syntax of a Python script. But in reality, language is far more complex. It is shaped by context, loaded with implied meanings, and influenced by the speaker’s and listener’s experiences and expectations. These subtleties can create ambiguities that make logical reasoning more difficult, but they also allow for the flexibility and nuance necessary for human communication and social understanding. First, we must address the challenge of determining whether a cognitive bias is at play in any given situation, depending on the mechanism involved. Second, even if it is a bias, that doesn’t automatically render it useless. When a bias malfunctions, it offers a rare glimpse into its inner workings—mechanisms that are crucial because they shape how we think and perceive reality.

Returning to the initial question: Was it a coincidence? Perhaps. From an objective standpoint, most likely. But there’s more to consider than just that perspective. Our cognition is inherently designed to detect and interpret patterns in the world around us. Granted, some of these patterns are false, correlational rather than causal. Yet the very fact that we can identify cognitive biases is a testament to their effectiveness. We notice biases primarily when they fail—and failures are the exception, not the rule. This cognitive machinery allows you to read and comprehend these words right now, to form a coherent perception of reality, and to maintain a narrative in your consciousness about what has happened, what is happening, and what might happen. These mechanisms connect disparate pieces of information into a meaningful whole. That’s why we should be cautious about hastily labeling something as merely a bias. Sometimes what we call a bias may actually reveal a pattern that isn’t immediately obvious to us. Perhaps that was the case with the man at my gym. Was our interaction a coincidence? In “objective reality,” it probably was. But from the perspective of my personal experience? Maybe, maybe not. It could have been entirely random, or it could have been a glimpse into something deeper—a pattern within reality too intricate to easily articulate.