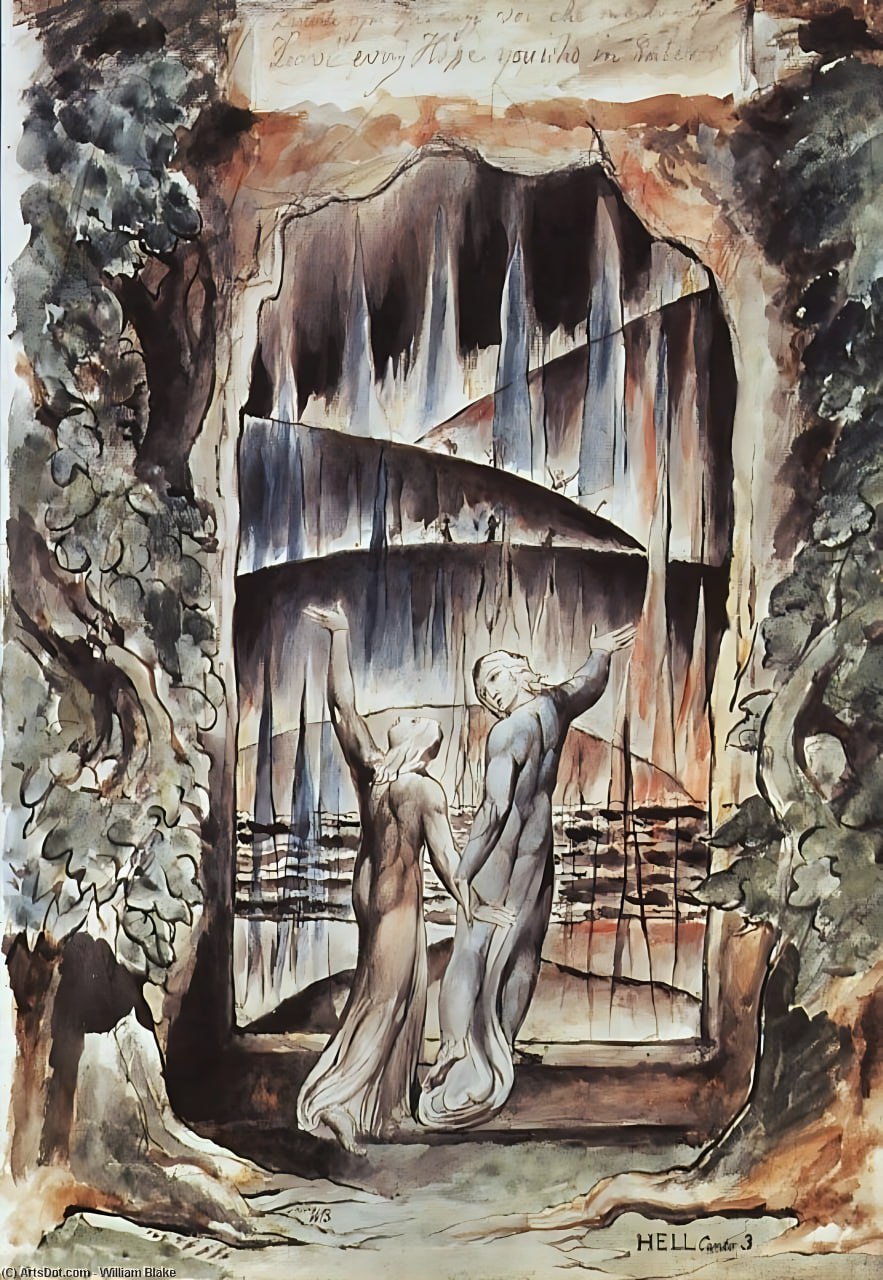

Dante and Virgil at the Gates of Hell, William Blake (1827)

Dante and Virgil at the Gates of Hell, William Blake (1827)

“That which Dante saw written on the door of the inferno must be written in a different sense also at the entrance to philosophy: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

-Friedrich Schelling

“In the end, nobody hears more out of things, including books, than he knows already. For that to which one lacks access from experience, one has no ears.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche

Volume 2

Chapter 4: Despair

No Longer Human

The hidden nature of life’s underlying depression continually surprises me. Beneath the fleeting highs of happiness, it seems as though each of us exists in a subtle state of existential dread—a fundamental, pervasive anxiety about the nature of existence and one’s place within it, often associated with feelings of meaninglessness and uncertainty. Sometimes it’s a mere whisper at the edge of awareness; other times, it’s a fog that envelops everything, obscuring meaning and direction. What’s most striking is that it requires no specific trigger. Heartbreak or pain isn’t necessary—simply relinquishing delusion and paying close attention is enough. In those moments, the dread of reality reveals itself, stripped of inherent meaning or attachment. Its lack of definition makes it impervious to any single interpretation, leaving you free to engage with it as you will, but its undeniable presence remains.

For many people, the only way to escape the weight of existential suffering is to cling to the desperate hope that prolonged ignorance will somehow make it disappear. This isn’t a conscious or rational strategy but rather an instinctive retreat—a way of distracting oneself or constructing comforting illusions to avoid confronting the harsh realities of existence. These illusions can take many forms: rigid belief systems, relentless consumerism, constant busyness, or the pursuit of fleeting pleasures. This avoidance, however, comes at a cost. It often involves constructing a delusion so vast and all-encompassing that it effectively replaces reality. The individual becomes consumed by these delusions, reshaping their perception of the world in ways that obscure their suffering but do not resolve it. The underlying existential dread remains, buried beneath layers of denial and distraction, ready to surface at the slightest crack in the façade.

I refuse such a fate. For me, the only path forward is to live with my sorrow, to confront it directly and without flinching. This choice is not easy—it requires a willingness to acknowledge the full weight of suffering and the unsettling implications it carries about the nature of existence itself. To deny sorrow is to deny a fundamental truth of life. Pain, after all, is inseparable from human experience. It reveals the fragility of our illusions and forces us to confront the limits of meaning and control. This acknowledgment is not an end in itself but a beginning. By confronting sorrow head-on, I create the possibility of overcoming it—not necessarily eradicating it, but integrating it into a broader understanding of life. Perhaps one day I will achieve this integration. Perhaps not. But the act of striving toward that victory is meaningful in and of itself. That striving is my commitment. It is all I can do. It is all I will do.

This attitude resonates deeply with the core teachings of Buddhism. Regardless of the specific validity of its doctrines or philosophies, Buddhism’s enduring appeal lies in its willingness to face the problem of suffering directly. It does not retreat into comforting fantasies or deny the reality of existential dread. Instead, it acknowledges suffering as an inescapable part of life and offers a framework for understanding and addressing it. This honest confrontation is a stark contrast to the illusions many other worldviews offer, which often revolve around denial or escapism. I can understand why people are drawn to these illusions. They are rooted in a deep psychological need for stability and certainty. These fantasies emerge from a prearticulate realm of human consciousness, where knowledge is still entangled with subconscious projections. In this space, ideas and beliefs are shaped more by emotion and instinct than by reason or evidence. These projections can offer comfort, but to approach a purer truth, they must be transcended.

The pursuit of truth, for me, is not about adhering to any specific claim or doctrine. Instead, it is about striving for truth itself—the highest possible value. This idea of truth serves as my guide and navigational map for reality. I accept truth as real and absolute, even as I acknowledge that my perception of it will always be imperfect. When truth manifests, it is inevitably distorted by my own limitations—by the biases, assumptions, and subjective filters that shape human understanding. These distortions are unavoidable, but they do not render the pursuit futile. Through vigilance and persistent effort, these distortions can self-correct over time. This process is not perfect, but it is sufficient to bring me closer to understanding. The journey toward truth is iterative: each effort reveals new insights and corrects past errors, gradually refining my grasp of reality. At its core, this process demands humility. It requires acknowledging the limits of my understanding while remaining committed to the pursuit of something greater than myself. It is an ongoing effort to balance the recognition of suffering with the hope of transcendence, to accept sorrow without succumbing to despair. This balance, imperfect as it is, allows me to live authentically, guided by a commitment to truth and a refusal to retreat into delusion.

Like many people, I’ve experienced periods of depression throughout my life. It’s difficult to measure my experiences against others—how they compare in frequency or intensity—because depression is a deeply personal and enigmatic phenomenon. It distorts your perception, pulling you into a spiral of negativity where pain and suffering dominate. Anything beyond this becomes diminished, reduced to insignificance. A close friend once suggested that accepting depression when it takes hold—making peace with it—might be beneficial. But that idea evokes a chilling association with depersonalization, a far more terrifying state in my mind, and one I consider even worse than depression itself. Depersonalization feels like slipping into a waking dream, where reality loses its solidity, and you move through life as if separated from yourself and the world by an invisible barrier. I’ve always been staunchly opposed to the concept of suicide, but during episodes of depersonalization, I’ve felt an unsettling pull toward non-existence. It’s not a desire for death, exactly, but rather a profound yearning for the release of simply not being.

I’ve often struggled to articulate why I instinctively reject suicide, even during moments of despair. Is it a drive to participate in life, however painful, for its own sake? Or is it some biological imperative designed to ensure survival? Perhaps it’s a combination of both, intertwined with a sense that continuing to exist is the safer gamble. Life, for all its trials, offers the possibility that my despair may be misplaced or that it may eventually lift. The cost of existence is undeniably high, yet the prospect of enduring holds an intrinsic value. Fortunately, life’s challenges have never driven me to seriously consider suicide. I recognize, though, that not everyone is so fortunate. Many face struggles far more acute, where the pain eclipses even the faintest hope of reprieve. For them, the choice to endure may not feel like a gamble worth taking.

This is the first time I’m revisiting a movie I’ve already seen. With a sense of greater maturity and knowledge, I hoped to uncover deeper insights this time around. I recall my initial viewing, more than a year ago—it left me astonished by the show’s profound depth. What shocked me even more was its relative obscurity. It’s not widely known, and even among those familiar with it, few seemed to recognize the masterpiece I believe it to be. This feels surreal, especially considering that it’s far from a trivial work; it’s an adaptation of one of the finest pieces of Japanese literature, and a highly respectable one at that. The show grapples with themes of social alienation and the construction of the persona, examining the hierarchy of the ego and superego, and—most crucially—explores the shadow. This connects to an earlier realization I had: beneath the surface of our lives, there’s a persistent undercurrent of existential dread. It often remains hidden but is ever-present, waiting to emerge.

I was apprehensive about watching this show while on LSD. The theme of suicide is a genuine concern for me in that state. Initially, I planned to watch it with others as a safeguard against any irreversible actions—perhaps that would have been wiser. Yet, here I am, alone. I’m unsure whether this is courage or recklessness. Likely the latter, though I suspect there’s some of the former, too. In a way, I see this as a trial, an existential challenge I feel compelled to face. People engage in extreme sports where their lives hang in the balance, and we tend to accept those risks because what they’re pursuing—the Dao, the fundamental nature and underlying order of the universe according to Chinese philosophy, we might say—justifies the danger. I see no reason why the same principle shouldn’t apply to spiritual or philosophical endeavors.

The show masterfully portrays the tension between the individual and the superego—the ideal self—but it goes even deeper, questioning the very meaning of having an ego at all. It’s striking how depression manifests differently in people: for some, it’s rooted in genuinely tragic circumstances, while others, whose lives appear outwardly fulfilling, are still weighed down by an undefined heaviness. It’s tempting to view this force as malevolent, but I hesitate to call it that. There’s something off about the connotations of agency and intent that the word “malevolent” carries. Whatever this force is, it feels profound and dark, but not intentionally harmful.

Throughout the story, there’s an emphasis on what it means to be human—as if existing isn’t enough; one must conform to a standard that feels external and absolute. But what validates this standard, and why should we feel beholden to it? This question evokes the despair of stepping beyond the familiar frameworks of culture and identity, only to confront the chaos of existence itself. It’s akin to facing the symbolic ouroboros: the ancient symbol of a serpent or dragon consuming its own tail, often representing cycles of life, death, and rebirth. In a Jungian interpretation, this symbol signifies infinity and wholeness while also embodying the concepts of undifferentiation, chaos, and the potential for transformation. It is the all-devouring cycle, eternally consuming itself, encompassing both creation and destruction.

While I hold a deep respect for Judeo-Christian culture and philosophy, I find myself increasingly drawn to Eastern ideals. This isn’t due to a fascination with the exotic; I’m always cautious of idolizing novelty for its own sake. Instead, this shift is rooted in personal experiences—particularly those involving psychedelics—coupled with an evolving understanding of psychology. Through these experiences, I’ve become increasingly convinced that the “I,” in the sense of a pure, independent ego, doesn’t truly exist. To those unfamiliar with Eastern religious concepts, this notion might seem extreme, but it’s less radical than it appears. In my limited and perhaps naive understanding of Hinduism, a similar idea is encapsulated in the assertion that we are all God. The only true “you” is consciousness itself—subjectivity in its purest form. You might call it the miracle of life, though even “life” is notoriously difficult to define. If you push hard enough, the line between living and non-living matter begins to blur, raising profound questions about existence.

The ego, then, is not some immutable core but rather a construct—a layered product of countless biological and sociocultural influences. I see no compelling argument to the contrary, especially when one considers the overwhelming evidence of how deeply our environment shapes us and how easily we can be manipulated without even realizing it. This is what fascinates me most about religion: its apparent ability to anticipate insights that neuroscience and psychology are only beginning to uncover. Religions seem to have arrived at profound truths—what might now be called neurobiological or phenomenological findings—through careful introspection and observation millennia ago. Yet in our modern era, dominated by a positivistic mindset, we are often too quick to dismiss these ideas as antiquated or irrelevant.

The stark divergence between Western and Eastern philosophies has been troubling me for some time. Both resonate with me as fundamentally true, yet I find myself struggling to reconcile them completely. The West places a strong emphasis on responsibility—on agency, action, and the moral duty to shape oneself and the world. In contrast, the East prioritizes acceptance—a surrender to the flow of existence, recognizing the impermanence of all things. While these perspectives may seem complementary at first glance, I can’t help but perceive them as fundamentally distinct. It would be convenient, even poetic, to claim that they can be seamlessly merged, that responsibility and acceptance are two sides of the same coin. But the deeper I study into their philosophical roots, the more they seem to create an unyielding divide—one that resists easy synthesis.

Christianity presents a powerful notion: the idea of original sin, of bearing responsibility for evil. This concept aligns with the emergence of free will triggered by self-consciousness, as depicted in the myth of Adam and Eve. The story symbolizes the emergence of self-consciousness in humanity. Initially, they exist in a child-like state of innocence, unaware of good and evil. Upon eating the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, they become self-aware, gaining the ability to discern right from wrong. This awareness brings not only moral understanding but also the capacity for empathy and intentional harm. By recognizing what causes their own pain, they understand what can hurt others, and with this knowledge comes the responsibility—and the choice—to act accordingly. From another perspective, original sin symbolizes humanity’s collective failure to embrace the divine, settling instead for the profane due to our inherent flaws. Consider all the ways in which you know you could improve but fail to act—this is your personal corruption. It’s unavoidable in the sense that perfection is impossible, but also, by definition, avoidable because you could always choose to be less flawed.

Voltaire once observed that every person is guilty of all the good they did not do. Responsibility, then, is inescapable. If each individual were to fully confront and rectify their own corruption, realizing their “divine” potential, we might achieve the “kingdom of God”—a state of collective, perpetual enlightenment. Yet we don’t, because we are corrupt. Not because someone else is corrupt, but because I am corrupt. And so are you. This insight is brilliant because it’s difficult to refute. The only way to deny it is to reject responsibility entirely and instead embrace acceptance—a notion that ignites the binary clash between these perspectives. At first glance, the idea of acceptance might seem suspect. It’s an appealing idea precisely because it lessens our accountability, so it’s easy to dismiss as weakness or even delusion. But what if we’re wrong? What if, no matter how fervently we assume responsibility for the world’s corruption, our efforts ultimately have no impact? In that case, we would simply be living in untruth, trapped in a perpetual state of self-deception. This hypothesis—that our efforts are futile—demands serious consideration. Perhaps we are all just rats on an ontological treadmill powered by an indifferent universe, and “enlightenment” means awakening to the illusion and ceasing the ceaseless running. From this perspective, you have no responsibility because there is no “you” in the sense of an agent with true autonomy. What you perceive as original ideas or personal behavior is merely the byproduct of biological and sociocultural forces. This is the essence of the Buddhist proposition: you are simply the observer, consciousness itself. Many people treat this notion casually, without exploring its depths. It took me a long time to internalize it, and I can’t pinpoint the exact moment it clicked. Still, the claim that you are consciousness—not in a poetic sense, but at the core of your being—rings profoundly true to me.

I haven’t had a full-blown mystical experience, and I still lean philosophically toward Christianity. Yet, during my most profound glimpses of awe—often in meditative states accompanied by music—Buddha in nirvana inexplicably appears to me. I don’t summon this image intentionally; it simply arises. I question myself carefully, as I don’t want to follow an idea blindly or without grounding. Even so, the notion that we are merely observers of external reality withstands every counterargument I’ve encountered. This contradiction genuinely troubles me. I can’t envision a scenario where both perspectives—responsibility and acceptance—are fully true without negating one another. Yet, a choice must be made. We cannot live without a fundamental framework, and the choice we make shapes the most essential framework of our existence. The subtlety of it makes it difficult to notice—it’s embedded in our culture, woven into our personalities, beliefs, and behaviors. It’s invisible yet ever-present. While this embeddedness provides structure and security, it also leaves us with the persistent uncertainty of whether we’re living a lie. Even if the division between Western and Eastern philosophies oversimplifies the complexities of day-to-day life, its roots run exceptionally deep. It undeniably manifests in personal behavior, shaping how we relate to ourselves, others, and the world at large.

It’s intriguing how the monster portrayed here evokes the Jungian shadow, though not perfectly. It leans less toward malevolence and more toward inadequacy—a sense of alienation and not belonging, a profound disconnection from the world. It’s not just a mismatch, but the anguish that arises from it. Perhaps the two are inseparable, two sides of the same coin. The shadow may become the shadow precisely because it is judged inadequate, cast out, and alienated.

Throughout the series, there are clear traces of Machiavellianism—a political theory advocating for pragmatic and, at times, unscrupulous tactics to maintain power. In psychology, it is characterized by manipulation, cunning, and a focus on self-interest over morality. However, I don’t interpret this as an endorsement of the philosophy, but rather as an exploration of its possibility. You—the ego—possess free will, at least phenomenologically, even if it’s ultimately an illusion. From this vantage point, you have the capacity to manifest any number of realities from an endless ocean of potential. Among these possibilities, there is at least one where you benefit personally, but at the expense of another’s suffering. The main character, though perhaps more sociopathic than most, reflects that shadow aspect within all of us: the corrupt, selfish dimension of our personality. Each of us can choose a path from this sea of possibilities that serves our own interests, fully aware of the harm it may inflict on others.

Most people, however, are dissuaded from such choices by the superego—the internalized moral compass that guides behavior. The problem is that many are naive about the true nature of the superego. People often assume it’s the ego making free choices, but that freedom can be illusory. Morality, deeply ingrained, becomes so automatic that it operates invisibly. This is what Nietzsche alluded to with his concept of the death of God. His warning was aimed not at believers, but at atheists. He warned how we don’t realize how the supposedly simplistic religious foundations of morality quietly sustain both society and individual behavior. Nor do we fully grasp the void left behind when they’re gone, or how to replace them. Nietzsche wasn’t definitively stating this as an inevitability, and neither am I. But it’s a possibility worth contemplating—a reminder of the fragility of moral and cultural frameworks we often take for granted.

Despite my apparent absorption in religious ideas and the seemingly sympathetic stance toward religion expressed throughout this manuscript, nothing unsettles me more than Christian apologists. Christian apologetics is a branch of Christian theology that aims to defend the faith against objections and criticisms. Apologists utilize philosophical, historical, and sometimes scientific arguments to provide rational support for Christian beliefs. It’s not their Christian affiliation, specifically, that bothers me, but rather the fact that they are the only apologists I’ve encountered. They make me uneasy, always coming across as disingenuous. I’d like to believe their deceptiveness is unintentional, yet I can’t escape the feeling that they are peddling falsehoods. Instead of genuinely seeking truth, they seem to distort it in an effort to defend pre-existing convictions, often employing convoluted semantic and logical gymnastics.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that many of them are highly skilled orators. Their rhetorical polish can be misleading, giving their arguments an illusion of substance. However, to any objective observer unclouded by their biases, the flaws in their reasoning are readily apparent. It’s reminiscent of debating conspiracy theorists: even when their arguments are internally consistent (which isn’t always the case), they often rest on premises that fail under closer inspection. The result is a system that may appear coherent at first glance but ultimately lacks structural integrity. This state of mind—the mental contortion required to force reality to conform to a predetermined worldview—is profoundly disheartening. It represents a tremendous investment of effort into defending a narrative rather than engaging with reality as it is. To see someone trapped in such a cycle, unable or unwilling to break free, is both frustrating and deeply saddening.

Since developing an interest in religion, I’ve become increasingly aware of how often it’s denounced in conversations. Criticisms tend to focus on its pathological elements, perceived irrationality, or the immense suffering it has historically caused. I completely understand these perspectives—there was a time, not long ago, when I likely would have shared them. However, it’s crucial to distinguish between religion as an expression of the “divine” and the way institutions practice it. Simply pointing out its flaws doesn’t negate its importance or potential necessity. I’m not claiming that religion is essential, but highlighting its shortcomings isn’t a sufficient rebuttal. Science, often seen as the antithesis of religion—or even its “cure” in modern culture—has its own set of flaws and limitations. This, I believe, is a blind spot for many atheists, particularly younger ones or those with limited scientific or philosophical experience. There’s often an implicit scientism at play. Scientism is the belief that the empirical sciences represent the most authoritative worldview or form of human knowledge, often to the exclusion of other viewpoints such as philosophy, religion, or the humanities. It involves a dismissal of the epistemic value of non-scientific perspectives and can be critiqued for overextending scientific authority.

I typically dislike the term “scientism,” as it’s frequently used by religious zealots to dismiss science entirely. Yet here, I think the term is warranted—not as an attack on science itself, but as a critique of an uncritical reverence for it. Science has limitations, and recognizing them doesn’t diminish its value. This idea draws from earlier critiques of logical positivism, which once dominated philosophical discourse but is less prominent today. Though the comparison may stretch the concept, I think it’s reasonable to extend these critiques to the collective tendency to overlook the practical flaws in how science is conducted and applied. Scientific practice, after all, is not immune to human error and systemic issues.

For instance, research papers not only can suffer from statistical flaws but also from a lack of transparency regarding methodologies and data, making it difficult for other scientists to replicate results. The peer-review process, intended as a mechanism for quality control, frequently falls short due to the limited availability of experts who are often overburdened with their own research and responsibilities. This can lead to less rigorous reviews and the occasional oversight of significant errors. Moreover, the existence of thousands of predatory journals, which charge authors to publish their papers without providing legitimate editorial and peer review services, further dilutes the quality of scientific literature. Replication, a cornerstone of scientific validation, is infrequently pursued due to the structure of academic incentives that favor novel findings over repeated studies. This lack of replication contributes to what is known as the “replication crisis,” particularly pronounced in psychology and other social sciences, where varying research designs and human complexities make consistent results challenging to achieve. Additionally, financial incentives can skew research outcomes. Funding from industry sources can influence the scope of research and the interpretation of results, potentially leading to conflicts of interest that may not always be disclosed. This issue is particularly acute in medical and pharmaceutical research, where the implications can directly affect public health policies and personal healthcare decisions. Statistical misinterpretations are also prevalent, including the misuse of p-values—a practice that is somewhat arbitrary and fixed across different fields and methodologies. Not to mention “p-hacking,” where data are manipulated until a statistically significant result is found, often undermining the integrity of research findings. Moreover, scientific research suffers from a massive over-representation of Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) populations in study samples, especially in psychology. This bias complicates the understanding of human behavior and cognitive processes, as findings derived from such samples may not generalize to non-WEIRD populations. Indeed, entire books could be—and have been—written about these pervasive issues.

However, dismissing science entirely because of these flaws would be absurd. Science remains our best tool for constructing an objective model of reality, and its imperfections don’t invalidate the method itself. The same principle should apply to religion. Just because organized religion has its pathologies or institutional flaws, it doesn’t inherently diminish what religion, at its core, seeks to express. Religion, like science, deserves a more nuanced examination. Its shortcomings should not overshadow its potential to address fundamental human questions or its ability to inspire meaning, purpose, and connection. Neither of them can be reduced to a simplistic critique without losing sight of the complexity of what they offer.

I’ve been contemplating what truly constitutes a persona. The simple explanation is clear: it’s a fabricated role adopted for a specific purpose, usually to shape how you’re perceived. In traditional psychology, a persona is the social mask or public face an individual presents to the outside world, influenced by societal roles and expectations. Originally it was a term from Jung, which reflects the part of the personality that one cultivates in response to external social demands. You can probably identify certain elements of your own persona without much difficulty. But the deeper, more troubling question is this: how can you truly tell? Given the limitations of self-awareness and the capacity for self-deception, how can you trust your own judgment about what is genuine? What assures you that you’re accurately distinguishing the authentic aspects of yourself from the persona? Couldn’t the “remnants” of your identity—those you assume are authentic—merely be additional personas you’ve yet to uncover? It’s evident that we all possess multiple personas, some more deeply ingrained than others. The more deeply rooted a persona, the harder it is to discern, and the more unsettling it is when you finally recognize it.

It seems likely—perhaps even inevitable—that you maintain personas for your own benefit, constructs designed to please yourself but originally shaped by external values you never fully realized were influencing you. If that’s the case, then what remains when you strip those personas away? Even if you reject the radical idea that your entire identity might be a persona—a notion that deserves serious consideration—what exactly constitutes your “true” self? Imagine trying to eliminate all social influences. What are you left with? In my view, nothing. There’s no final essence to reach. Some might suggest “biology” as the core of identity, but this doesn’t resolve the issue, as biology exists outside of conscious identity—it’s another external factor. Jung believed that we begin as pure persona and gradually shed it as we mature, but I’m not entirely convinced. Perhaps in striving to reach the non-persona essence of the psyche, you end up constructing yet another persona.

I recall a mundane moment a few years ago that brought these ideas into sharp focus. It was an ordinary day, and I was at the checkout counter paying for groceries. Suddenly, I realized I was juggling multiple personas simultaneously: the “grocery-shopping customer,” the “late-teenager running errands,” the “guy trying to seem cool for the attractive cashier,” the “Portuguese person,” the “Western individual,” and more. Dozens—possibly hundreds—of roles, all at once. This wasn’t an abstract realization; it tangibly influenced my behavior. I could trace it to the smallest details: how I positioned my hands, the way I moved, my facial expressions, my tone of voice, and the specific words I chose. I couldn’t articulate exactly how these subtle actions connected to larger conceptual roles, but I sensed the underlying patterns influencing me. Some personas were consciously performed, but others felt deeply internalized—roles I had created to validate myself, shaped by external standards I had absorbed unconsciously. The realization felt uncanny.

A clinician, observing my behavior in that moment, might have diagnosed me with social anxiety. From the outside, my hyper-awareness and internal analysis of the situation could easily appear as a nervous overreaction or fear of judgment. But that wasn’t what I felt at all. I wasn’t anxious, afraid, or overwhelmed by negativity. My actions—paying for groceries, bagging them, exchanging brief pleasantries with the cashier—were entirely smooth and unforced. Yet internally, I was struck by something entirely different: the absurdity of it all. It wasn’t just the situation that felt absurd; it was my own role in it. I suddenly felt profoundly detached from myself, as though I were watching a play unfold. But I wasn’t just watching—I was also acting in the play, and somehow, I was also aware of the artificiality of both roles. I could see myself playing the part of “the grocery shopper,” but I could also sense a deeper construct: I was enacting a scripted performance tied to countless invisible influences—cultural norms, personal habits, societal expectations. These scripts dictated how I moved, spoke, positioned my hands, and even the thoughts I chose to acknowledge. The whole situation felt like a carefully choreographed routine that I hadn’t consciously designed but was nonetheless executing perfectly. And then it hit me: I’m not really in control. This wasn’t a gradual realization but a sudden, almost jolting awareness. It was as if I had assumed all my life that I was holding a gaming controller—a device that allowed me to navigate and direct my actions, decisions, and even my identity. I had believed this controller was plugged into some console somewhere, connected to some deeper sense of self, providing the guidance and agency I associated with being me. But in that moment, I realized the controller wasn’t plugged in at all.

The analogy made the situation feel even more uncanny. I had been “playing the game” of my life with the confidence that I was the one directing my movements and shaping my reality. Now, confronted with the possibility that my perceived agency was an illusion, I felt a kind of disorientation that was neither panic nor relief—it was pure confusion. If I wasn’t controlling my actions, then what was? Was I simply a product of unconscious patterns, social conditioning, and biological instincts? Was everything I identified as “me” just a series of automatic responses dressed up as intentional choices? This realization flashed through my mind in a matter of seconds while I stood there, bagging my groceries. Yet those few seconds felt expansive, as though time had slowed to accommodate the weight of the realization. My body continued its task mechanically, completing the mundane routine of paying for groceries, while my mind wrestled with the implications. As I walked away from the counter, one question surfaced with startling clarity: What do I do now? It wasn’t rhetorical, nor was it some abstract philosophical musing about the nature of existence. It felt immediate, grounded, and practical—an urgent question born out of the realization that the foundation I had relied on for my sense of self and agency was suddenly exposed as illusory. If the controller I thought I was holding had never been plugged in, then what was the next step? Should I pick it up again and pretend it worked? Should I embrace the illusion for the sake of continuity, even knowing now that it wasn’t real?

The analogy grew even more troubling the more I thought about it. If the controller had always been disconnected, it meant I wasn’t directing my life at all. My actions, my personas, my choices—all of them were being shaped by external forces and unconscious patterns that I didn’t fully understand. Yet, paradoxically, I still felt as though I was making decisions. This dissonance left me wondering: is the illusion of control not only necessary but inevitable? Do we have to believe in the controller, even if it’s not real, just to keep functioning? This wasn’t despair, nor was it relief—it was something stranger and harder to define. It was the unsettling experience of seeing the machinery of my life laid-bare. For years, I had moved through the world assuming I was both the operator and the architect of my life. But now, with the inner workings exposed, I was left questioning whether the machine could—or even should—keep running. And if I wasn’t the one controlling it, who or what was?

I’ve recently decided to try DMT on my 30th birthday—the day after I turn thirty. I’m not entirely sure why this idea came to me, but it feels significant, like a milestone worth marking with a transformative experience. I’ve wanted to try DMT for some time, yet I keep postponing it. Part of the hesitation stems from a belief I’ve long held: such an intense and complex experience demands thorough preparation. By “prepared,” I don’t just mean having the right set and setting, though those are crucial. I also mean being intellectually, emotionally, and perhaps even spiritually ready to engage with what DMT might reveal. The problem, I’ve realized, is that readiness has no clear benchmark. How do I know when I’ve read enough, thought enough, or experienced enough to confidently declare myself “prepared”? I can’t. There’s no definitive point where one can say, “Yes, now I’m ready.” Waiting for such certainty might mean waiting forever. So, I’ve decided to set an arbitrary deadline: my 30th birthday. I have seven years to prepare. That seems like ample time to read, reflect, and cultivate the understanding I feel is necessary. If I’m not ready by then, I suspect I never will be. At that point, I’ll take a leap of faith. This decision isn’t just about the deadline itself; it’s also about curbing any impulsive desire to rush into the experience. Psychedelics, especially something as powerful as DMT, demand respect and careful consideration. By giving myself a clear, distant goal, I can temper impatience and approach the experience with a steady, deliberate mindset.

Some might see this approach as overly cautious, but I would argue the opposite. My recent mystical experience has only strengthened my conviction that these substances must be approached with care and reverence. If that experience had occurred just a year earlier, I don’t believe I would have had the intellectual framework or emotional grounding to integrate it as I have now. Instead, I would have been completely disoriented and likely too shaken to ever consider psychedelics again. Even with my current perspective, the experience was destabilizing in many ways—a profound upheaval of my assumptions and perceptions. But it was manageable, something I could process and learn from. Without the proper grounding, I might have been consumed by fear or confusion, unable to make sense of what I encountered. And these experiences don’t come close to the immersive intensity of DMT. From what I’ve read and heard, DMT takes you beyond anything LSD can offer, plunging you into realms that defy description and comprehension. It’s not just a journey inward—it’s a total dissolution of self, a direct confrontation with the unknown. The prospect excites me, but it also reinforces the need for respect and preparation. DMT is not something to approach lightly or impulsively. By giving myself seven years to prepare, I’m granting myself the time to grow into the kind of person who can face that experience with clarity and openness. I want to approach it not with reckless curiosity, but with a sense of readiness—however incomplete that readiness may ultimately be. When the time comes, it will still require a leap of faith, but at least it will be a deliberate one.

Previous: Volume 2 Chapter 3: Demons