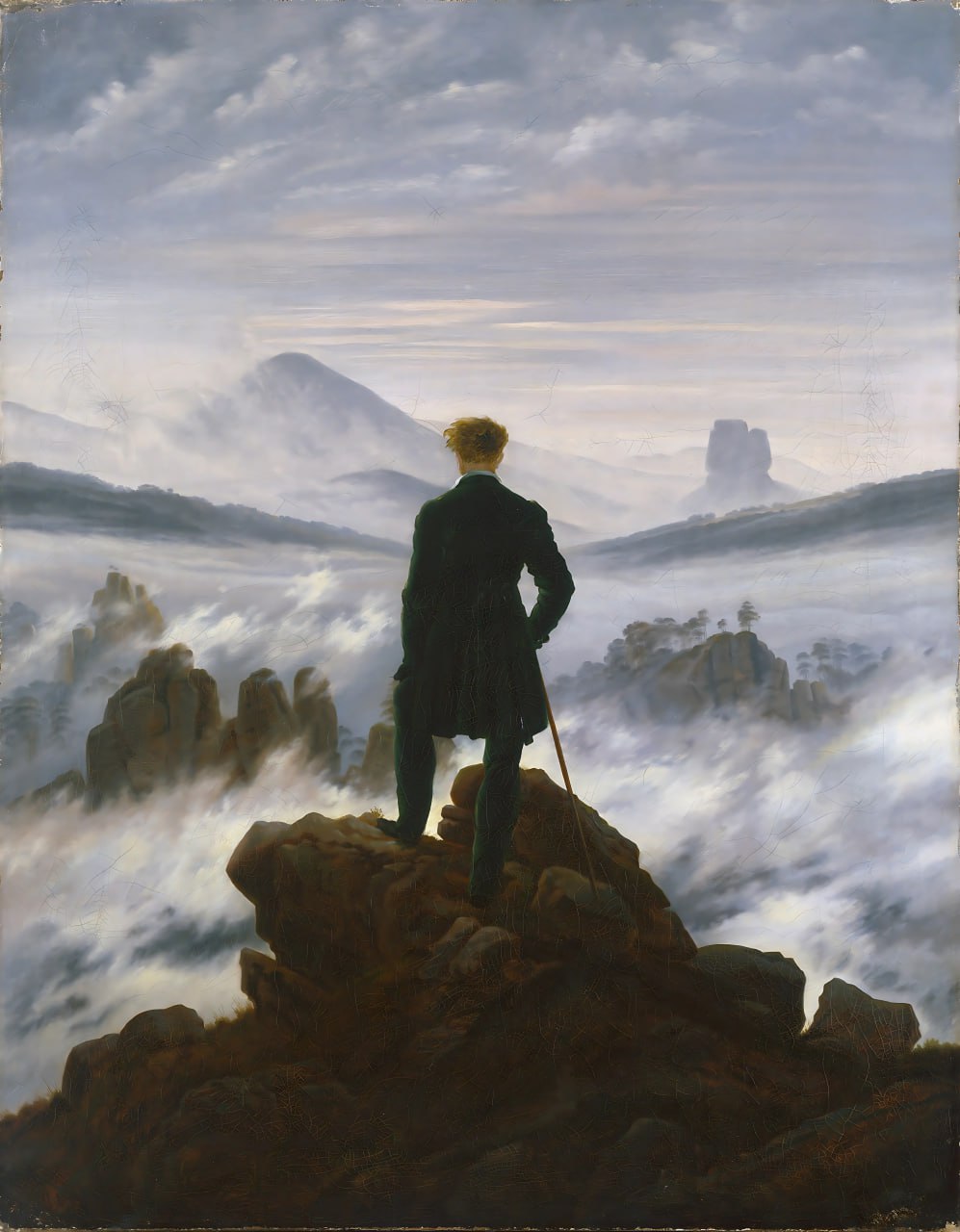

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1818)

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1818)

“I know nothing, nothing. I not only have no answer to give, but I haven’t even found a satisfactory way of propounding the questions.”

-Simone de Beauvoir

“All are lunatics, but he who can analyze his delusion is called a philosopher.”

-Ambrose Bierce

Volume 1

Chapter 2: The Unknown

Psychedelics are like exams: you should not undertake them unless you are prepared. Each experience builds on the last, reflecting the culmination of what you have learned so far. Think of it as feeding raw intellectual data into a machine—an intricate mechanism capable of assembling that data into something more meaningful. Beyond intellectual input, each “exam” also contributes to your personal growth, shaping the outcome—the intellectual and emotional “product” of the machine. Thus, the process of preparation and engagement with psychedelics involves two layers of enhancement: not only does the quality of your input improve through continuous learning and refinement, but your capacity to process and integrate those insights—the machine itself—becomes more sophisticated.

With this in mind, there is a responsibility to provide the process with sufficiently valuable information. In a sense, you must be “worthy” of activating the machine. If you approach the experience unchanged since your last engagement, the endeavor risks becoming unproductive, a recycling of old material rather than an exploration of new territory. However, if you have grown in that time, then the experience becomes a valuable gauge of your progress. Defining improvement is no simple task, but deep introspection will often yield clarity. Ask yourself: Have I grown? Am I better than I was before? A negative response is not a failure but a signal that further time and effort are needed. Growth is not instantaneous, nor should it be rushed. The process unfolds in its own time, and patience is an essential component of the journey.

I just had a vision—so vivid and striking that I attempted to capture it in a drawing, though my artistic skills, especially while not sober, fell short of the image’s grandeur. What I saw in my mind was as detailed and alive as a CGI-rendered scene from a modern film. It began with a desert: vast, infinite, and desolate—a landscape stripped of life except for a singular point of activity at its center. The scene divided itself horizontally, with the ground forming a boundary between the visible and the hidden. Above this plane, swirling lines and curves floated like tumbleweeds, representing fragments of information drifting aimlessly. The vision was a paradox, at once natural and digital, as though an organic interpretation of an abstract, mathematical reality. It was distinctly computational yet undeniably alive. At the center of this barren environment stood a cluster of block-like structures. They resembled buildings but exuded an industrial, mechanical quality, as though they were components of an automated factory—cold, precise, and unfeeling in their design. At the heart of this system revolved a massive wheel, a central mechanism whose relentless rotation powered the entire scene. This wheel seemed almost sentient, its motion imbuing the surroundings with an eerie vitality. Above the structures, beams of light shimmered—a radiant aura symbolizing consciousness. The contrast between the cold, mechanical blocks and the vibrant energy above them was striking, as if the system were struggling to assert its own aliveness. To the west of the scene, a clenched hand emerged, gripping the drifting lines of information and pulling them toward the central mechanism. The motion was predatory, like a spider capturing its prey. The hand consumed the fragments of information and fed them to the system, which expanded with each piece absorbed, growing in size and complexity. Beneath the visible plane, a dark abyss loomed—a cavernous void representing the unknown. This was the subconscious: a hidden wellspring of processes and forces that drove the machinery above. It was a potent reminder of the limitations of perception, of the unseen forces that permeate and shape the visible world. Reflecting on this vision, I interpret it as a metaphor for how individuals and societies interact with the unknown. It captures the process of extracting meaning from chaos, integrating it into our collective understanding, and using it to build something greater. It is a cycle of growth: a relentless effort to reach into the void, retrieve fragments of insight, and integrate them into the fabric of our shared reality.

Stories carry ideas, and it is the resonance of an idea that grants a story its meaning. Even if other aspects of the story—its plot, characters, or style—fail to captivate, a single resonant idea can render it profoundly significant. This resonance arises from the subjective interpretation of the audience, reflecting their personal interaction with the story’s underlying ideas. Meaning, therefore, is inherently individual; what speaks deeply to one person may not move another. Our interpretation is shaped by the entirety of who we are—our reality, our experiences, and the knowledge we carry.

Every story exists within a specific context, created by an individual whose identity is shaped by their knowledge, experiences, and culture. These elements are imprinted on the narrative, influencing the ideas it conveys and the way those ideas are expressed. As readers, we engage with these ideas, but not passively; we filter them through our own perspectives, which are similarly informed by our unique realities. This dynamic interplay between the author’s intent and the audience’s interpretation means that a story’s meaning is not static or fixed. It evolves as it interacts with each new reader, shaped by their personal lens.

Through this interpretive process, stories give rise to archetypes—universal patterns of human experience that transcend individual narratives. Archetypes like the hero, the divine mother, or the trickster resonate so deeply because they exist beyond the specific details of any single story. They embody shared human realities, abstractions distilled from the collective experience of countless generations. These archetypes feel timeless because they emerge from the most profound layers of our shared consciousness, connecting individuals across cultures and eras. This is why stories possess such enduring power. They are far more than mere entertainment. They serve as vessels for ideas that connect us to the broader human condition, allowing us to glimpse the universal within the particular. Through the lens of a story, we are invited to see not only the author’s reality or our own but something far greater. Stories bind us to the shared essence of what it means to be human, offering a bridge between the personal and the collective, the transient and the eternal.

I find myself reflecting on the numerous books about religion now populating the bookshelf to the right of my desk—a collection that would have surprised, even repelled, my younger self. Why this shift? Why this newfound curiosity? As a child and early teenager, I dismissed religion—and anything that wasn’t strictly rational or scientific—with thinly veiled contempt. I couldn’t comprehend how anyone could derive meaning from such beliefs. My conclusion, which seemed inevitable at the time, was simple: I was intelligent, and others were simply less so. This reductionist explanation, though it satisfied my youthful arrogance, began to unravel as I matured and encountered people whose intellect far surpassed my own, yet still embraced religious or spiritual frameworks. These encounters forced me to reconsider my assumptions. While I once dismissed such beliefs as arbitrary or irrational, I began to notice a deeper consistency—a pattern that demanded investigation rather than dismissal.

People do not cling to random beliefs or assign meaning to arbitrary concepts. There is a discernible logic to what resonates with human beings, even if that logic is not immediately apparent. Exploring the reasons behind these patterns offers a far richer and more meaningful approach than simply labeling them as foolish. Even if these beliefs ultimately lack objective grounding, their near-universal appeal suggests something fundamentally human. The pervasiveness of religion and mysticism across cultures and eras speaks to an enduring psychological or existential need—one worth understanding.

If you perceive the world as blue, while someone else perceives it as red, the first step is to question your own perception. Could you be mistaken? Never underestimate the possibility of your own delusion. Challenging your own perspective, even when it feels unshakable, is an essential exercise in humility and intellectual honesty. However, if after careful examination you remain certain of your blue perception, the next step is to turn your attention outward: why red? Why not yellow, green, or pink? The prevalence of the red perception, particularly when it contradicts your own certainty, points to a pattern worth investigating. Rather than dismissing this alternative perspective as misguided or valueless, consider what its persistence might reveal.

We are often quick to devalue perspectives that deviate from our own, assuming that their difference inherently implies a lack of merit. Yet, the very persistence of such differing views suggests that they are neither arbitrary nor insignificant. They emerge and endure for a reason. Exploring that reason offers a far more productive approach than mere dismissal. In doing so, we open ourselves to understanding the broader forces at play—forces that may reveal new dimensions of meaning, even if they initially challenge our certainty.

This line of thought leads to a series of profound questions: Why do humans possess such a deep-seated need for alternative interpretations of reality? Why is this phenomenon so universal, persisting across vastly different cultures and epochs? Why are humans capable of mystical experiences, as evidenced by the effects of psychedelics? What is the nature of these experiences, and what do they reveal about the human mind? What evolutionary advantages, if any, might such experiences confer? Why do people cling so fiercely to beliefs, even when confronted with evidence that challenges their validity? Furthermore, what is the relationship between religion and morality? How do these two forces shape and influence one another? Addressing these questions is crucial to unraveling the nature of religion itself. And understanding religion is not merely an academic exercise—it is a gateway to understanding ourselves, our desires, our fears, and the frameworks we construct to navigate existence.

Coming to terms with religion has been a long and ongoing process, perhaps even an unfinished one. To explain, I need to provide some context about my childhood. From as early as I can remember, I was considered the “smart” kid. This label, coupled with a natural intellectual curiosity, became a central part of my identity. Yet, I’m still uncertain how this perception developed. Was it an accurate assessment of my abilities, a persona I crafted to gain attention and praise, or merely the one aspect of myself I felt could hold value in social situations? Although I wasn’t isolated or friendless, I was undoubtedly more introverted than most—a trait that persists to this day. My own biases and the fog of memory make it difficult to pinpoint the origins of this identity.

Even as I grew older, I was often cast as the rational one in any group—a label that, for better or worse, continues to shape how others see me and how I see myself. It is a label I have come to resent in some ways, recognizing the pressure it brings and the limitations it imposes. My ongoing struggle with needing external validation of my intelligence has been one of my more persistent personal battles. It was my first LSD experience that brought these patterns into sharper focus. The trip catalyzed profound introspection and allowed me to trace how this identity had been constructed over the years, piece by piece.

From as far back as I can remember, I never believed in God. I maintained a steady skepticism toward the supernatural, a perspective that was unusual for a child. My parents weren’t atheists in the strictest sense, but neither were they deeply religious—especially my father, whose disinterest in religious rituals subtly shaped my outlook. Despite this, I attended Catechism classes and completed my first communion, an experience I found deeply uncomfortable and vaguely unsettling. Looking back, it struck me as cult-like, though I doubt I had the language or understanding at the time to fully articulate why it felt that way.

By the time I was approaching adolescence, perhaps even earlier, I began grappling more seriously with the concept of religion. Much like the red and blue analogy I referenced previously, I couldn’t reconcile how others could genuinely hold religious beliefs. This cognitive dissonance disturbed me deeply; either I was wrong, or they were. At the time, I couldn’t conceive of my perspective being flawed, yet I struggled to accept the possibility that so many others could be mistaken. This internal conflict unfolded against a cultural backdrop where religious belief was still far more common than it is today. My discomfort was compounded by my self-perception as someone inherently “smart” and “rational.” I drew a conclusion that, at the time, felt almost inevitable: I was simply more intelligent, more logical than those who adhered to religious faith. It was a tidy resolution, but one that, in retrospect, reveals much about my youthful arrogance and my need to protect a fragile sense of self.

However, my social interactions at the time were primarily limited to family and school peers. As I grew older and discovered the internet, my perception of my own intelligence underwent a profound shift. While I didn’t think of myself as unintelligent, it became glaringly obvious that I wasn’t particularly special. The sheer number of individuals who exhibited intellect far surpassing my own was both humbling and disorienting. Over time, I also encountered extraordinarily intelligent individuals who were, to my surprise, religious. This directly challenged my earlier assumption that religious belief was inherently a sign of lower intelligence or irrationality, leaving me grappling with a contradiction that took nearly a decade to fully untangle.

The first breakthrough came as I deepened my engagement with science, particularly through my professional work, which required rigorous interaction with research methodologies. Through this, I was frequently confronted with the concepts of cognitive biases and their influence on human thought. Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from rational judgment, leading to illogical conclusions or skewed perceptions. These biases often emerge from mental shortcuts, known as heuristics, which simplify complex information processing. Understanding how these biases operate clarified how even seemingly logical individuals can arrive at flawed conclusions—and that intelligence alone is no safeguard against them.

I also examined the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance, the psychological discomfort that arises when holding contradictory beliefs or encountering evidence that challenges one’s worldview. This concept, introduced by Leon Festinger, explains the mental tension people experience in these moments, which often compels them to either adjust their beliefs or rationalize inconsistencies to reduce discomfort. The recognition that cognitive dissonance and biases are inherent to all human cognition—not just the thinking of others—was crucial in reshaping my perspective on rationality.

For a long time, I genuinely believed that my reasoning was purely logical, unaffected by the biases and inconsistencies I so readily identified in others. Yet the reality is that no one operates with perfect rationality. While I may have been more rational than average, true, unblemished logic is an unattainable ideal. Accepting this was humbling but also freeing, as it allowed me to move beyond the oversimplified notions of intelligence and rationality I had clung to for so long. Intelligence, I realized, does not exempt anyone from the vulnerabilities of belief, bias, and contradiction—it only shapes the ways in which these vulnerabilities manifest.

In my younger years, I equated rationality with skepticism, evidence-based reasoning, logical thinking, and selecting the most plausible hypothesis. Irrationality, by contrast, included belief in God, ghosts, demons, magical beings, or general superstitions. However, over time, I came to understand that this dichotomy was overly simplistic. The reality is far more nuanced. I made irrational decisions every day; they were just smaller, less dramatic, and less metaphysical, which made them easier to overlook. This realization profoundly impacted my understanding of both myself and the world. It became clear to me that perceiving reality solely through a materialistic lens was a deeply flawed approach. As humans, we lack the capacity to fully grasp reality in such a reductionist manner. While it is possible to extract materialistic information when we focus on it, doing so misses the richness and complexity of lived experience.

This insight directly ties back to the question of rationality. The very existence of the scientific method serves as a reminder of our inherent subjectivity. Science, as a discipline, exists to counterbalance the biases and distortions that naturally arise from our subjective perceptions. It does this by systematically eliminating—or at least mitigating—those errors. This process underscores a fundamental truth: a scientific worldview is not innate to human beings. If it were, science would not need to be a specialized discipline; it would simply be how we engage with the world in our daily lives. But that is not how we function—not even remotely.

The rigorous nature of the scientific method highlights just how challenging it is for us to achieve true objectivity. If objectivity were our natural state, we would simply look at the world and perceive reality as it is. But the human mind is not constructed that way. Instead, our perceptions are shaped by cognitive biases, emotional influences, and subjective interpretations that cloud our understanding. The complexity and precision of scientific procedures are necessary precisely because they compensate for our natural inability to see the world with unfiltered clarity.

This realization became even more apparent when I began studying history. We often have a tendency to view history with a sense of condescension, focusing on the so-called foolish mistakes of those who came before us. It is difficult to resist the feeling that we are inherently smarter or more advanced than previous generations. But that sense of superiority is an illusion. Our retrospective analysis is filtered through a modern, materialistic lens, one shaped by the intellectual and scientific advancements of recent centuries. Past generations, however, lived within a vastly different conceptual framework. Attempting to analyze ancient texts or cultural practices as though they were scientific documents is not only unproductive but fundamentally misunderstands the context in which they were created. These texts emerged from a time when science, as we now understand it, did not exist in isolation from other forms of knowledge. Science and religion were often intertwined because both represented their contemporary understanding of the world. If we had been born into those cultures, without the advantage of modern scientific advancements, we would likely share their worldview. Their understanding of reality was no less valid in its context than ours is in ours. Thus, when examining history, it is imperative to strive for empathy and a genuine understanding of how previous generations perceived the world. Their understanding of reality, shaped by their environment and limitations, differed profoundly from our own, and we should approach their beliefs and actions with humility rather than judgment.

The final piece of this puzzle fell into place when I realized that religion serves multiple fundamental human needs—philosophical, emotional, and spiritual. This was something my younger self completely failed to appreciate. Whether the metaphysical claims of religion are scientifically verifiable is irrelevant in this context. Religion addresses aspects of the human condition that extend far beyond material evidence or logic. Dostoevsky captured this idea beautifully when he wrote, “Men still are men and not the keys of a piano.” His point resonates deeply with our understanding of human nature. For instance, babies are highly vulnerable to death from neglect, even when all their physiological needs—food, water, warmth—are met. Social interaction, human touch, and emotional connection are not minor details; they are core components of what it means to be human. These needs are deeply ingrained within us, as essential to our survival and well-being as the material necessities of life. Religion, in many ways, speaks to these deeply rooted aspects of our nature, offering meaning, connection, and a framework for understanding the complexities of human existence.

My earlier belief—that from my supposedly superior rational vantage point, religion was nothing more than an irrational delusion—was profoundly misguided. I now see that I, too, act irrationally, though in different ways. I, too, have philosophical, emotional, and even spiritual needs, though I hesitate to use the word “spiritual” because of its susceptibility to misinterpretation. If my life experiences had shaped me differently, I could very easily have been religious myself.

My studies in psychology have deepened this understanding, revealing how rationality is often subordinate to emotion. Reason, as a function of human consciousness, is a relatively recent evolutionary development. When the prefrontal cortex, the seat of rational thought, clashes with more primitive, emotion-generating areas of the brain, it frequently concedes. Rational thinking likely emerged because it enhanced our ability to solve problems and to secure what we desire from the world. But it is not the master of the mind; it is often merely a tool wielded by emotion-driven motivations.

I recall my younger self naively believing that scientific thinking was self-evident, a natural and inevitable conclusion for any intelligent person. In hindsight, I recognize the profound ignorance of that assumption. The scientific mindset seemed obvious to me only because I inherited it from my culture and society. Yet this “obviousness” is anything but natural—it is the result of centuries, even millennia, of painstaking human ingenuity. Back then, I viewed people of the past as unintelligent, dismissing their beliefs and actions as foolish. I was wrong. They were just like me. Perhaps, on average, they were slightly less intelligent due to challenges like malnutrition or limited intellectual stimulation during childhood, but they were not fundamentally different. They were constrained by the same cognitive and emotional architecture I have, yet without the privileges I enjoy. Born into a world with limited access to knowledge, I would almost certainly have shared their beliefs, their superstitions, and their mistakes.

We often fail to fully appreciate how astonishingly recent the development of modern science is. For the overwhelming majority of human history, we relied almost entirely on emotion and intuition rather than reason to navigate the world. Rational thought, while powerful, is effective only when supported by adequate knowledge to inform decisions. In contrast, emotional “thought” and decision-making operate more like intuition—a tendency to lean toward certain outcomes without a clear, logical rationale. This intuitive process arises from subconscious assumptions shaped by past experiences. Although these assumptions can often be flawed, they still tend to yield better results than random chance.

The form of science we recognize today, grounded in systematic methodology and empirical evidence, has existed for only about 600 years, emerging during the Enlightenment. While earlier civilizations engaged in scientific inquiry, their methods were comparatively rudimentary. Early civilizations observed the sky and recorded celestial events, but their methods lacked systematic empirical processes and were not based on reproducibility or controlled experimentation. These early astronomers relied more on observation and the recording of patterns without the rigorous testing and validation that characterize modern science. What defines science in its current form is not merely the pursuit of technological or theoretical advancements, but the disciplined process through which conclusions are reached. This systematic approach is what distinguishes modern science from its early precursors and ensures its ongoing evolution.

Even the modern understanding of science is far more recent than we often realize. The concept of falsifiability—that a hypothesis is scientifically valid only if it can be proven false, and that researchers should actively seek to disprove their theories rather than confirm them—was famously advocated by Karl Popper, a philosopher of the mid-20th century. Encountering this principle for the first time felt like a revelation. While similar ideas existed before Popper, he was the first to underline its critical importance to scientific inquiry. His work elevated falsifiability to its current status as a foundational axiom of modern scientific thought. It’s astonishing to consider that such a cornerstone of science is less than a century old.

To place this in perspective, complex societies like Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt emerged 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, a time when mammoths still roamed parts of the earth. Humans, as a species, have existed for approximately 200,000 years. Even this definition of “human,” while useful, is somewhat arbitrary. If we set aside cultural distinctions, the physiological and cognitive differences between us and our recent ancestors are minimal. Our lineage stretches back millions of years, connecting us to a common ancestor shared with apes. While the comparison may feel uncomfortable to some, the truth is that if a modern human were raised in isolation within a jungle environment, without social or cultural learning, their abilities wouldn’t vastly outstrip those of a highly intelligent chimpanzee by very much. Our perceived intellectual dominance is not inherent but the product of cumulative cultural and technological knowledge, passed down and expanded upon by countless minds over millennia. Recognizing this fact deepened my understanding of how easily our emotional needs can overshadow reason.

This realization does not contradict my critical view of religion, particularly when it is interpreted literally. However, it has helped me shed an “us versus them” mentality. I now see that my capacity for illogical thought is no less human than anyone else’s. This humility parallels the pursuit of Truth. While absolute Truth may be forever out of reach—or at least, beyond full human comprehension—it does not diminish the value of striving for the most accurate understanding possible. Similarly, while I am not and cannot be a purely logical being, this does not absolve me from striving toward logical thought or rejecting irrationality when I recognize it. My perspective may still contain flaws and is subject to change, but it reflects the most comprehensive and meaningful understanding I have achieved so far.

A couple of years ago, my aunt passed away, and I attended her funeral. It was a modest gathering of family and friends, held in a small chapel that felt quiet and solemn. Near the end of the service, a priest began the formal funeral rites. I remember the ritual involving prayers, blessings, and a few words about my aunt’s life and her passage into the afterlife. As soon as it started, I felt an overwhelming surge of discomfort. It grew into something like anger, and I couldn’t control the urge to leave. Even though I knew it would be seen as rude, I stepped out of the room and waited in the hallway until it was over. At the time, my understanding of religion and tradition was superficial, as I had not yet started studying philosophy, religion, or psychology. Looking back now, I feel a sense of shame and regret for my actions that day. Though it wasn’t a major disruption, and my relationship with my aunt wasn’t particularly close, I still feel that my response was poor—a failure to show composure and respect. It’s an incident I hope never to repeat.

More recently, I attended my younger cousin’s baptism at a local church. I had hoped that the time I spent reflecting on religion and exploring different philosophies would help me handle this event with greater respect. I went in with a sense of preparation, telling myself that I would observe calmly and try to understand the ceremony’s purpose. However, as soon as the choir began to sing and the readings from scripture echoed in the church, I started to feel deeply unsettled. The sensation reminded me of the funeral, but this time it felt even more intense. There was a moment when my mind began to race, telling me I didn’t belong there, that I should leave. I found this reaction surprising and disturbing because I thought I had grown past that visceral discomfort. In a strange twist, when I framed it in religious terms, it felt like I was in the presence of something dark or malevolent, which is odd given that these ceremonies are meant to celebrate faith and community.

I’ve tried to understand where this strong reaction comes from, and I believe it has to do with the associations I’ve developed over time. Propaganda music and speeches from oppressive regimes—like the Soviet Union or North Korea—have always given me chills. The choreographed nature of those events feels frightening to me, like a display of power aimed at controlling people’s minds. During the baptism, I noticed the congregation rising and sitting in unison, following a shared routine. That coordinated behavior made me think of Nazi rallies, where large groups move together in a precise, almost mechanical fashion. These memories and parallels rose up in my mind and made the whole experience unsettling. It wasn’t just mild discomfort; it felt like a deep, instinctive existential alarm going off inside me.

One particular moment stood out. The priest, looking out at everyone, asked if they believed in the resurrection of Jesus and his divinity. The congregation, almost as one, responded with a clear, synchronized “Yes.” It wasn’t the question itself that bothered me. Rather, it was how the group responded in perfect unison. It brought to mind the image of a large crowd accepting a statement without question, and that image disturbed me. For a second, it felt like I was trapped in a dream where individuality had vanished, replaced by a single voice repeating what it was told. I’m aware this reaction might be extreme. A baptism, after all, is a significant religious sacrament, meant to welcome a person into a faith community. It has deep roots in tradition and belief, and many find comfort and meaning in these rituals. Intellectually, I can understand that. I can see how these ceremonies can build unity, provide moral guidance, and offer support to believers. Yet this understanding doesn’t fully vanish the profound discomfort I felt on a deeper emotional and subconscious level. Perhaps it’s a residue of my younger self’s strong disdain for religion, a feeling that, despite my evolving views, might never entirely leave me.

Previous: Volume 1 Chapter 1: Divine Journeys

Next: Volume 1 Chapter 3: Finding the Roots

Date: 12/4/2017